|

SEASON'S GREETINGS!  Welcome to the Bayport Times.  In this issue you'll find my interview with David Browne, the artist responsible for many of the British covers; David Palmer's A Last Talk With Leslie McFarlane plus new collectible discoveries and more.

In this issue you'll find my interview with David Browne, the artist responsible for many of the British covers; David Palmer's A Last Talk With Leslie McFarlane plus new collectible discoveries and more.

Bayport Times Sixth Anniversary

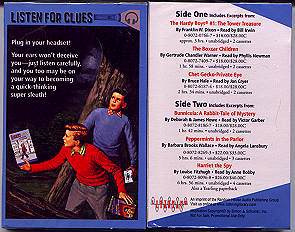

Hardy Boys Audio Tapes

Hardy Boys Record Price!

Hardy Boys Digests Needed!

Give Books For The Holidays!

Articles Needed |

|

|

Audio Sampler Cassette

|

|

Recent additions to the Hardy canon All These Titles Are Available For Sale From Amazon.com - Just Click! | |

| Visit My Used Book Sales Page Many Collectible Series Books Hardy Boys, Nancy Drew, Tom Swift & More! | |

|

The Secret Of The Soldier's Gold (#182) - Grade: A-

The Hardy Boys and their family are headed to Lisbon, Portugal and when a friend asks them to search for gold hidden there by a relative during World War II, they agree. While hunting for the hidden gold, they are pursued and almost captured by neo-fascists and corrupt police and almost killed during a thrilling motorboat chase. The Hardys keep up their investigation and turn up the missing gold in a twist ending. Double Jeopardy (#181) - Grade: A-

Typhoon Island (#180) - Grade: B-

Passport To Danger (#179) - Grade: A

The Mystery Of The Black Rhino (#178) - Grade: C

The Case Of The Psychic's Vision (#177) - Grade: F

In Plane Sight (#176) - Grade: B

|

David Browne was the artist for many of the later British Hardy Boys editions. |

How old are you?

When did you start painting?

Did you go to art school? If so, where?

When did you start painting Hardy Boys cover art?

Who hired you?

How did you get the job?

Which covers did you paint?

Are you still painting Hardy Boys art?

What medium did you use?

How long did it take to complete a project, on average?

How was the subject of the design selected?

Can you describe the process of creating the cover art from assignment

to acceptance?

How much did you get paid per cover?

Did you ever read the books you created the covers for?

Did you ever do the art for Nancy Drew or other juvenile series?

UK HARDY BOYS Series 'E'. Painted c.1991-92 by David Browne and Kenny McKendry

UK HARDY BOYS Series 'E'. Painted c.1991-92 by David Browne and Kenny McKendry

01 The Mystery Of The Aztec Warrior E - shadow of two men falls on boys tied up. The boys aren't tied up, though I don't remember why I positioned them like that. This was the first brief I was given, and the first one which I painted, around late 1990 / early 1991. 02 The Arctic Patrol Mystery E - Joe pulls Frank from open fissure. Second one painted. Taken from a travel guide of Iceland! My agent thought it was "too detailed". 03 The Haunted Fort E - boys attacked by lake monster. Third one painted. It's a smaller painting than 1 & 2, the publishers were beginning to push deadlines. 04 The Mystery Of The Whale Tattoo E - boys fight men by house. First one painted by Kenny McKendry. Armada weren't happy with it, and gave me most of the series, but eventually Kenny's paintings went down much better than mine. With only one artist working on the series full time, our Hardy Boy models grew up_ with the blond one growing a ponytail, developing a beergut etc. Kenny kept his compositions bright and simple, and coped better with the decreasing quality of the photographic reference. 05 The Mystery Of The Disappearing Floor E - boys carry Jack Wayne from plane crash. One of mine. I play the part of Jack Wayne! 06 The Mystery Of The Desert Giant E - boys run from plane flying overhead. One of mine. One of the smallest in scale, anything to speed up the process! 07 The Mystery Of The Melted Coins E - Joe threatened by Blackbeard. One of mine. Blackbeard is my step-father with a beard grafted on! 08 The Mystery Of The Spiral Bridge E - boys threatened by grizzly bear. Kenny's second. I think he did it at the same time as the Whale Tattoo. We were given the briefs in batches of three or four, the reasoning being that we could share costs for the photographic sessions and shoot several covers in one go. 09 The Clue Of The Screeching Owl E - Frank carries boy from lake. One of mine. That's Kenny being carried. The blond Hardy Boy was already becoming hard to arrange photo sessions with. 10 While The Clock Ticked E - boys climbing on roof top. One of mine. My stepfather's there again. The roof was my neighbour's as viewed from our kitchen window! 11 The Twisted Claw E - Frank climbs from path of rolling logs. One of Kenny's. One of his later ones, a great painting. It went down so well that it was used in our agency's catalogue. 12 The Wailing Siren Mystery E - man and wolf threaten boys. One of mine, from early 1992. My agent wanted a change of style... "colourful as you can get it, then add a bit more colour." Hence the psychedelic look. For this batch we only had the dark Hardy boy to work with, meaning that no.2 had to be taken from earlier model shots. 15 The Flickering Torch Mystery E - boys examine scarecrow. One of mine, from mid 1992, and one of my last ones. I had a real loss of confidence around this time, caused by the increasing difficulties of putting the pictures together. This painting had to be virtually redone. The boys had grown so much that by now they looked useless, and of course they also felt too old to be hamming it up for the cameras.. I had to use old reference material. 16 The Secret of The Old Mill E - boys in car, boat house explodes behind them. One of mine. To get my confidence back I went for a huge, spectacular painting. Chet is played by me... though I had to broaden myself on the painting! 17 The Shore Road Mystery E - grenade thrown through window towards boys. One of mine. Painted in early 1992, not one of my favourites! 18 The Great Airport Mystery E - boys open crate, man hiding behind door. One of mine. From the 'psychedelic' batch. I'm the bad guy in the background. 19 The Sign Of The Crooked Arrow E - Joe on bucking horse. One of mine. One of my very last, from late 1992. 20 The Clue In The Embers E - boys with skeleton (Mr Bones). One of mine. From the 'psychedelic' batch. The skeleton was cardboard! 23 Footprints Under The Window E? - The boys are shown hiding behind stones in a graveyard, as a sinister figure (me again..) sneaks past. One of mine, from early 1992. 24 The Crisscross Shadow E - Frank climbs rope, hand with knife. One of mine, from early 1992. The bad guy (guess who... ME!) is trying to cut the rope. The background is Death Valley. 25 Hunting For Hidden Gold E - boys in cave shine light on gold. One of Kenny's. 26 The Mystery Of Cabin Island E - boys carry man in snow storm. One of Kenny's, from mid 1992. This one went down very well, and was held up as an example of how the series should be painted. 29 The Hooded Hawk Mystery E - man slaps boy tied to chair. One of mine, from mid 1992. The bad guy is me, yet again, the idea shows my frustration with the series by this time..."Stop growing your hair, and get rid of the beer belly!" 30 The Secret Agent On Flight 101 E - Frank clings to plane wing. One of mine, from early 1992. 33 The Viking Symbol Mystery E - boys in path of stampeding bison. One of mine, from late 1992, one of my last ones. No photo models by this stage, so that's me as the dark Hardy Boy, and Kenny (with blond Hardy Boy grafted on!). We photographed the scene in his living room! 34 The Mystery Of The Chinese Junk E - boys swim away from Junk. One of mine, from late 1992, one of my last ones. Photo reference taken from earlier batch (Danger In The Diamond). 35 The Mystery At Devil's Paw E - boys in water tied to pier support. One of Kenny's. I think that he used Brighton pier as the backdrop. 36 The Ghost At Skeleton Rock E - boys in water, shark swimming past. One of mine, from April 1992. One of the most difficult to paint, the flag was photographed floating in my bath. 37 The Clue Of The Broken Blade E - boys leap from cable-car. One of mine, from early 1992. That's me trying to kick Hardy no.2 off the ski lift. 38 The Secret Of Wildcat Swamp E - boys run from path of rolling boulder. One of mine, from 1992. Me in my garden, with a Hardy Boy head grafted on. The 'boulder' was about 4 inches across. 45 The Shattered Helmet D - boys find helmet in broken boat 46 The Clue Of The Hissing Serpent D - boys in plane in storm These were painted by Kenny in 1987, I'd forgotten that he had done some of the previous set (with the badge motif in the corner!) He had a different agent at the time, and it's a complete coincidence that he got the job twice in a row. I can't remember why he only painted two or three covers this time around... For models in the plane cockpit he used himself, and his flat-mate Justin. I may have taken the photos... though all I can really remember is Kenny's fiancee killing herself laughing at us. 86 The Sky Blue Frame E - boys in path of car 1991 Kenny's. 87 Danger On The Diamond E - boys run from exploding truck 1991. One of mine, the fourth one of the series which I painted. I thought it odd that the series went 1,2,3, then 87.... and gave up counting after that. We were certainly told that we'd have to do all 87 in the series, and weren't told why it suddenly stopped. The reasoning for using us in the first place was that we had similar styles (we've known each other since primary school), and they wanted a uniform style throughout the series, with the same models etc. I heard no more after I showed my agent how the boys were growing too old looking to pose for us, and I seem to remember that anyway they both were unavailable to model from September 1992 onwards (when they started university). The series gave me a small income for a while afterwards anyway. Our covers were used in 2-in-1 versions and then 3-in-1. I have proof covers for the following 2-in-1s, which all use my artwork: Hooded Hawk/Secret Agent On Flight 101; Viking Symbol/Chinese Junk; Crooked Arrow/Clue in The Embers; Disappearing Floor/Desert Giant; Shore Road/Great Airport and 3-in-1s: 1993 Viking Symbol/Chinese Junk/Devil's Paw; Mystery Of The Silver Star/Programme For Destruction/Sky Blue Frame The former uses my Mystery Of The Melted Coins artwork on the cover and spine, the latter has a gaudy '3 BOOKS IN ONE' plastered across it, and uses Kenny's 'Sky Blue Flame' artwork on the cover, plus my Mystery Of The Melted Coins artwork on the spine (for some reason!) I then discovered quite a few of our paintings in a remaindered book shop, on the covers of more 3-in-1s on the 'Diamond Books' label. I hadn't been paid, so my agent visited them. The publisher was a cheap offshoot of Collins, and had been given rights to our work by them, without informing us. Nancy Drew was painted by another artist at my agency, called David Kearney, the lucky devil. Click Here To See More Sample British Art By David Browne & Kenny McKendry |

A Last Talk With Leslie McFarlane |

|

In the late thirties and forties he wrote dozens of radio plays, and in 1944, after two years with the Department of Munitions and Supply, he was invited by John Grierson to join the National Film Board. During the next fourteen years he wrote, produced or directed (often all three) twenty-eight documentary films, winning several awards and an Oscar nomination. In 1958 he became head of the television drama script department at the CBC and wrote many television plays for that and other networks. He continued to produce occasional books (and revisions of earlier works) for children, and some of these later writings are reviewed elsewhere in this issue of CCL. Ironically, in view of this enormous output, McFarlane is probably best known now as the original Franklin W. Dixon. He eventually produced twenty-one Hardy Boys titles, a task which he accepted as necessary hackwork to support more ambitious literary activities, and from which he derived no royalties. A recent estimate puts annual sales of this series at nearly two million copies. Leslie McFarlane has provided a witty and irreverent account of the experience in his autobiographical Ghost Of The Hardy Boys (1976). Over the last twenty years the books have undergone a controversial revision and modernization by other hands. The interview which follows took place in a motel room in Hamilton, Ontario, on April 23rd, 1977, the day after McFarlane had received an award at the "Canada Day" festival of Canadian literature held at Mohawk College in Hamilton. The short robust figure of previous years was much thinner, but Leslie McFarlane's conversation was still lively and vigorous. The transcript of the interview was intended to be sent to McFarlane for clarification and amplification of certain points, but death intervened. To preserve authenticity, editing has been kept to the minimum required for reasonable clarity and economy. PALMER: I want to start with the comment you made yesterday about the disapproval of the Hardy Boys books by librarians. I wonder if you could expand on your reaction to that. McFARLANE: Well, I had an irresistible impulse yesterday afternoon, when I mentioned the fact that the Hardy Boys stories had been banned in the Stratford-Waterloo area, to say, "This now classes them with Penthouse magazine." Yes, this business of banning books is nonsensical. Of course, my only interest in the matter is entirely academic, because I get no royalties from the books, and the books are re-written books from my originals and so on. But the banning or withdrawing of books from circulation in libraries is a really potent weapon because you're getting into censorship there. Certainly, I do believe in a certain degree of censorship for magazines of the nature of Penthouse, because many of them are gross, and put out purely to make money catering to depraved tastes. So I am not entirely against censorship; I think a certain amount of control is desirable here and there. But so far as the Hardy Boy books are concerned, they'll take care of themselves. If they are banned, kids will go out and buy them anyway. They're pretty powerful market-wise you know. Kids will buy what they want. I would probably rather see them get the books from the library free. Mind you, it costs the library a good deal of money to maintain a set of Hardy Boys books because there are about 50 or 60 of them and kids wear them out. They're not in very durable bindings, and I recall when we lived in the Town of Mount Royal quite a number of years ago, they used to use several sets of Hardy Boys books every year and thought nothing of it. But really, are the books written for a librarian, a teacher, or are they written for children? To the writer it's an important question. Now some librarians are extremely good, and others are-oh boy, they make the writer of children's books shudder when he confronts them. They're very prissy, very straight, very solemn. They think a book should educate. There's no reason a book should educate. If it amuses children, makes them laugh, takes them out of themselves, that's often sufficient. The job of librarians is to select the sort of things that children are going to read, which gives them an enormous influence you know. I think it's more important for the librarian, say, of the children's section of a public library to pass a pretty rigid examination than it is for a school teacher, since school teachers are probably limited to one age group. But the librarian goes on and on dealing with kids of all ages over a long period of time. PALMER: There's a great contrast between the Hardy Boys books and your more recent books about children, such as The last of the Great Picnics or A Kid in Haileybury. Is that the result of the constraints involved in working for the Stratemeyer Syndicate? McFARLANE: Well yes. You wrote what was wanted. You know, you wrote to a market. But I simply assumed, well, he knows his business, and I think he did, and certainly his business was to sell a great many books, or a large number of copies of any book. So he knew his business that way. But the outlines were rather, you know, set pattern things. The same story over and over again, which leads me into one comment on writing for children. In telling stories to small children (my own youngsters included, when they were growing up) I discovered they wanted the same story all the time. I imagine librarians are familiar with this manifestation. You tell them the story of Jack and the Beanstalk, and the next evening: "I'll tell you another story. I'll tell you the story of Cinderella." "No, I want Jack and the Beanstalk." So you tell them the one about Jack and the Beanstalk, and he gets up to the palace and the giant says "fe-fi-fo-fum, I want the blood of an Englishman," and you make an error in that and miss the "fe-fi-fo-fum," a look of dismay crosses the youngster: "How about the fe-fi-fo-fum?" They remember every detail, and they want it exactly, they want the facsimile of the story you've told. This is really rather an odd thing about youngsters, and of course I think it follows through, say, in a series of books-once you've written a book that is successful they want the same story all over again. PALMER: It must be a little odd for you to be known mainly as the person who ghost-wrote the Hardy Boys stories, when you've had such a long and distinguished career in other kinds of writing and activities. McFARLANE: Right from the beginning I tried to avoid any association of my name with the Hardy Boys, but in spite of everything it seems to have pursued me ever since people discovered that I did write the books. And I think too there was something I didn't particularly care for, and that was: here's a Canadian who has made good in a difficult field. Because I was a Canadian, newspapers would take this thing up. Well, whether I was a Canadian wasn't the point. But there is such a chauvinistic attitude on the part of various areas of the press towards anything Canadian. Well, look at the current story about Groucho Marx's troubles: his nurse is a Canadian. This is being played up, as if this reflected some additional glory on this country. Here's a Canadian whose books have sold fifty million copies. Well, so what? It's a big sale, fifty to sixty titles in several languages. But I can't say that I was particularly proud of this association. I wrote the books as part of making a living, and they were only a very small, fractional bit of what I have written over a period of sixty years. I don't regard myself as a writer for children in any way. It happens that in writing all the kinds of things I have written, some books fall into that category. Gage and Company would send me a note and say: we would like, say, a story for one of our school readers, and we would like it to be a hockey story, and could we have, please, a girl heroine? Well, this is a rather nice slant, and you figure, well why not? So I sit down and contrive a story with a girl as a heroine of a hockey story. They read it, they're delighted with it, and it's printed. I've done a number of things for Canadian publishers in that line. But once again, that doesn't make me primarily a children's writer. After all, all my television plays are for adults. There were a great many of them. Al my radio plays were for adults. There were a great many of them too. And magazine stories for McLean's magazine, for Argosy, for Country GentlemanΈ for Liberty, all kinds of stories adult stories. So why they pick me out as a children's writer I don't know. PALMER: And the Film Board. I did one film for children for J. Arthur Rank. They wanted to set up a children's film series in England and they wanted to have the films produced if possible in other countries Australia, South Africa, Canada and so on. So they sent their man over to Canada and the Film Board I met this gentleman and I was asked if I could turn out an outline; so I gave them an outline of a film called The Boy who Stopped Niagara and they liked it very much and immediately financed the film, and I wrote a script and directed it. It had modest success. It wasn't as good as it would have been if I had made it say three or four years later when I had had more experience in direction. But it was quite successful. It was nominated for some sort of an award over in Europe I think, in Belgium or someplace. PALMER: I want to tell you how much I enjoyed your autobiographical book, Ghost of the Hardy Boys, I thought it was one of the most enchanting and amusing books I've read for a long time. McFARLANE: That's very kind of you to say so because the reviews have been remarkable, especially the American reviews excellent, and you know really heart-warming. And the mail, it's just fantastic. In the book I quoted a man who worked as a book reviewer on the Springfield Republican, but I couldn't remember his name, so I wrote to the Republican and asked them: "Can you tell me the name of the man who reviewed books fro the Republican in 1926?" To my surprise, they said they had no record of him whatever, and they didn't know. So I had to put that in the book. Then this man wrote me a letter and said he was a very good friend of this chap, and the spoke of the few months that I worked on the Republican But the mail has been all the way from college professors to little kids of eight and nine years of age, from practically every state in the union. PALMER: I noticed the enthusiastic response yesterday of several women who said their sons had read all the Hardy Boy books, and one of the things that was said brings me back to the question I asked before about the libraries. I asked one of those ladies afterwards whether her son had gone on from the Hardy Boys to read other kinds of books. She said yes he had, he reads voraciously, all kinds of things now. Yet the common objection is that such books don't stretch children's capacities, that children will be content with reading them and never graduate to anything else. McFARLANE: I don't think it's valid at all. Reading is a habit. It's a very good habit to get into, and I feel that if that kind of book is any use at all, it's the fact that it hooks the youngster on reading, and "hooked" is the word. It's almost like a dope addiction. You know, they want to read everything in sight. But this is a good thing. You can't spoil any youngster by too much reading I think. There's such a difference. I was brought up on the English children's literature, Chums and Boy's Own Paper, which would come out in annual volumes. Well, in my book I mention how powerful they were. The style of those stories was quite different to anything you would read on this side of the water. They were enchanting books, plenty of action and good background. I wouldn't vouch for their historical accuracy and so on, and the authenticity of the books. But nevertheless they were excellent stories and could keep any boy spellbound. But they were different, very different. They had an entirely different breed of cats writing books and stories for boys on the other side of the water. PALMER: Do you think your books were to some extent a fusion of the two influences the boys' books from England and those from the States? McFARLANE: I would think so, probably, yes, because I grew up reading Horatio Alger of course, and the usual things we would get here, as well as the annual volumes of Chums and The Boy's Own Paper. For some reason Canadian boys much preferred Chums to The Boy's Own Paper. English lads preferred The Boy's Own Paper. They still sell them at the Old Favourites Bookshop in Toronto. They keep regular supplies of them coming in from dissolved estates. So many people keep these old copies. People pounce on them. They sell very quickly. PALMER: You mention in the autobiography the thrill you had at the idea that you could actually be Roy Rockwood and some of those other ghost names used by the Stratemeyer Syndicate. Did you read a lot of those books? McFARLANE: I would read a few of them, and other kids would talk about them. You would read Bomba and the Jungle Boy, a straight imitation of Tarzan of the Apes pretty good, pretty fast moving things. But by that time I was getting into Tarzan of the Apes the real Bomba. PALMER: To get back to the autobiography for a moment: why did you focus on the Hardy Boys? McFARLANE: Well, I went to one publisher several years ago with what I thought was a saleable autobiography, and I said to him, "frankly I quite realize that I am not important enough as a writer to rate an autobiography." And he didn't say, "Oh no, that's a stupid attitude, of course you do." He didn't say anything of the kind. In fact he agreed with me, and I think I was quite right, I wasn't that well known or that important. But I said I thought that maybe if we hooked it on to the Hardy Boys, which is a very well known thing, it would go. Well he didn't really think so. But I went ahead and did it anyway, and the script hung around for a while. I didn't even send it anywhere, and my son read it and he called me up and said, "Why are you leaving this lying around? I think it's very good. Let me send it to my publisher." He had a publisher who was doing his hockey books then, so I said, "Well, do what you like with it. I just wrote it to get it off my chest." So he sent it to the publisher, and the next thing I knew I had a contract with a great deal of re-writing. Sandra Esche, the editor, and I were on the telephone every night for two or three weeks. An enormous amount of work. That girl really put a lot into it. She is a very good editor, and I can't say this of all the publishing houses. Some of their editors are dreadful. I go every week on Friday when I am in Sarasota to a luncheon. It's a little writer's club. Sometimes the membership goes as high as thirty, sometimes as low as eight or nine. The base or nucleus are writers living in Sarasota, but of course during the tourist months there are many writers from New York, editors an others, who will come and visit us. These writers are John D. MacDonald, MacKinlay Kantor and until recently Nick Kenny and Richard Jessup [author of] The Cincinnati Kid, and people like that. We talk writing, but not too much; we usually play liar's poker for about two hours. Anyway there's a general feeling among the writers in my group that so many big houses hire girls fresh out of Vassar or some other girls' school, and these girls are charming, beautiful idiots. They shouldn't be allowed inside the doors of a publishing house. They simply know nothing about the business. But they think they know it all, and I can recall my friend, MacKinlay Kantor, being driven to an absolutely white hot frenzy on one of his recent books, when one of these gals sent him a long list of instructions on how to write his book, how to change it: and of course he's only been writing for over fifty years and has won a Pulitzer Prize and so on. He was so mad that he took the book away from the publisher. I have had my experiences too. But why is it that the publishing industry will let itself be undermined in one of the most crucial areas, the editing of scripts, by employing such inexperienced help? Their heads are in the clouds. Something makes them daffy to think they are working for a publishing firm, that they have an influence on the destinies of the big writers and so on. It's very dangerous. But every one of these writers agree with this the editors are a big problem. It's largely because they're too young, too experienced in so many cases. PALMER: I want to ask you about The Last of the Great Picnics. There is a section in there with a rather patriotic tone about Sir John A. Macdonald. McFARLANE: I have a strong feeling about the First of July, and I was delighted to read in the paper the other day that it seems to be coming back the celebration of the first of July as a national holiday. Now why this is happening in view of the current political situation I don't know. But you know, for quite a while the celebration, or even the name Dominion Day this had a context that was unfavourably regarded, and the celebration of a national holiday on the first of July was beginning to fade out. Now it appears to be having some official encouragement, and I am delighted because I think it's one thing that can help pull people together, celebrating the same thing at the same time from coast to coast. The Last of the Great Picnics had two sources, and both of them were quite important. One was an excellent book by Donald Creighton. He has written the life of Sir John A. Macdonald in two big volumes, and in his book he described Macdonald's big come-back on a series of political picnics an instance of how the picnic was an important political function in those days. Well, I am old enough now, and I was young enough then, to recall the political picnic because I attended them as a youngster with my father and my uncles or whatever, and they were very interesting. Of course to a small boy they were interesting because there was always a great deal of food, and you can't beat country cooking And so the political picnics helped bring Macdonald back after the Pacific scandal. This was in Creighton's book, and while reading it I thought, this is really something. Actually at the time I was looking for subjects for a radio play back in the thirties or early forties. I wrote a play called Something to Remember, based on the political picnic and Sir John A. There was one radio version on which The Last of the Great Picnics was based, and then there was a half-hour radio version and a one-hour television version after the book came out, in which the art was done by children, or by artists imitating the art of children I don't know which. It had many runs on CBC. But after the radio play I felt that I hadn't really exhausted the subject, I hadn't really done it justice. So eventually I turned it into a book. This was how the thing evolved. It came from that source and it also came from my own recollections of picnics and of county fairs when the balloonist's act was an almost inevitable feature of the day's entertainment. And there I found an unexpected difficulty. I found there was practically no literature on the matter. I wanted to find out how the aeronaut managed this business of jumping from a gas-filled balloon and transferring himself from one parachute to another, swinging from one to another, in the course of his descent. I could find no literature on it and I still haven't been able to find any precise description of how that was managed, and I often wonder if I imagined it. He would go up in a balloon which was filled with hot air, they would have a fire on the fair or circus grounds, and so on. The balloon would rise and he would be in a basket, and he would then step out with a parachute and a cross-bar, and of course the parachute would open up and he would come down maybe a few hundred feet, and then somehow he would swing and be on another parachute of a different colour, a different kind, and he would come down via three parachutes. As a child of course I remembered this very vividly but I don't remember the technique or the detail of it. So this is the part of the book that has caused me a great deal of wonderment, and I have made many efforts to try to ascertain from the records how this was done but I could find very little on it. To a child you see, this was a most memorable thing. This aeronaut coming down from the sky in a series of parachutes a terrific act! And then as well as these memories I read through a great many of Sir John A.'s speeches to get background for this, and one of them did talk about Dominion Day and Sir John A.'s convictions that people should celebrate it and honour it. So I clipped one paragraph out of one of his speeches and inserted that into the book. PALMER: That speech reflected your own feelings about Canada and about being Canadian? McFARLANE: Oh yes. I wouldn't have used it otherwise, because it gives me a chance to reach a lot of kids with this Dominion Day thing - that this is a day to be remembered and honoured and kept and so on, and it certainly marks me as an old Conservative and square and what have you. But I couldn't care less about that. I believe in it and I think it is a very good thing, especially now. PALMER: How did the fact that you were the author of the Hardy Boys come out? McFARLANE: Oh, I mentioned it to Nathan Cohen, who was a colleague of mine at CBC back about 1957-58. Nathan was chief drama editor, and I succeeded him in that spot when he went over as drama critic at the Star. We used to sit around in the morning over coffee and talk about everything because we were interested in about the same things, the same kind of literature and so on, and I let drop the fact that I had written the early Hardy Boys books. But of course at that time he was working with me at CBC so I didn't think there was any danger in letting him know this. The moment he went to work at the Toronto Star he sent a reporter round to interview me, with a photographer. There was a tremendous flash all over the front page. Then I began getting calls and so forth. Kids began coming for autographs and a van of boy scouts would show up at the house, and I never had the heart really to turn down youngsters, even if they were asking me to autograph books I hadn't written at all you know, re-written Hardy Boys books. I never had the heart to turn them down; I would autograph them, anything to save a kid the embarrassment of thinking he's had the errand for the wrong reason or purpose. If the kids got a kick out of it, I'd go along. I don't think really there's anything wrong with that at all. PALMER: But Brian [McFarlane] knew much earlier that you had written these books? McFARLANE: Well actually he didn't. He saw the books around, but he really wasn't very curious about them. He didn't know that I had written them. As I described in the book, he asked his mother one day why I kept all those books around and she said, "Well. Don't you know? He wrote them." He couldn't believe it. PALMER: Could you tell me about the revisions that you did to the stories that have appeared in the new Checkmate series? McFARLANE: That is a rather complicated subject because some of the revisions were made to modernize and speed up the books and so on. But because it was obvious that these dealt with hockey thirty years ago, I couldn't really go into very much revision, because you would have to recast the entire story. So I would do just enough to make it palatable to a modern youngster. It wasn't the happiest of jobs I will say. There was an enormous amount of work that went into that series. I wasn't very happy. I don't like revising old stuff. Now, let's say, modernizing or going over something like The Last of the Great Picnics, that isn't too bad. You'll always find things you want to change a little bit. For example, in the book I would like to change the order of some of the sequences if I ever get a crack at doing a second edition of them. I would like to do that as I did in the radio version of the same book. I changed everything around and now I have the radio copy which did work. It worked well. But with the Checkmate things it was a little difficult to deal with a dated story, one which was obviously dealing with hockey in the thirties without actually saying so. It was a little tricky, and Sandra Esche worked with me on this thing, but we did try to bring out a series of books that would be palatable to people. I wrote a great many stories for the pulp magazines in the thirties and for Sport magazine. I had an editor who was very sympathetic to my kind of work, and he would buy a hockey serial every winter and a bike story every summer. He also bought a long series of stories which I thought were humorous about a stumblebum prize fighter called Baldwin, a Joe Palooka type of guy, touring the country with his uncle and a large bulldog named Pansy, picking up fights along the way. This was going very well, and it was earning me a very neat one hundred dollars a story whenever I cared to sit down and write them I found them easy to write until one day the editor said, "Well, you know, the secret of writing humour is to find an editor who agrees that your stuff is funny. After that it's simple. My trouble is, I think your stuff is funny but a lot of my readers don't. They keep writing me letters asking me when I'm going to get rid of McFarlane and this stupid character Baldwin Now the letters against are beginning to outweigh the pros: I'm afraid Baldwin will have to go." But he had had a pretty good run. But this bit about humour is an odd thing you know. The whole secret is to find an editor who agrees with you, because humour is the touchiest thing in the world and it all depends on the point of view. Look at Wodehouse. It's rarely that his situations are all that comical, but that point of view of his is marvellously funny, to most of us at any rate. PALMER: If I can return to the Checkmate series again, I sense that some of the violence has been toned down a bit. There are odd situations where people fall off cliffs or whatever without being pushed. McFARLANE: Well actually back in the thirties there was no particular feeling about violence in fiction. The hero got slugged over the head but he always recovered. No, I think my plotting ability wasn't all that good back in those days. I was still a youngster you know, trying to make a living and to find editors who would buy my stuff. Street & Smith, of course, was an enormous firm with dozens of magazines, all hungry for copy. They just called it copy and they would buy almost anything if it was in English and it read reasonably well. When the Depression began, things began folding up a little bit on the markets, so I went down to New York and talked to an editor at Street & Smith and I said, "You know, you haven't been buying very much of my stuff lately. Now what can I do to improve?" He reached over and opened the door of the office safe, which was a little larger than that television set, and it was jammed with manuscripts right to the top. He said, "They are manuscripts that I have bought already, and I must find space for them somehow in the magazine. That's why I'm not buying stories right now." There must have been a thousand stories in that safe. PALMER: That must have been rather discouraging. McFARLANE: Yes, and a writer relies very heavily on his confidence in what he's doing. It's a very strong thing. It means that you simply assume that you are pretty good, and here you go, you're going to write a story and you're going to prove it, and if you haven't got that confidence if you write the story feeling, well, maybe it could be better, then you're going to start re-writing and re-writing and fixing it up and the whole thing will be a mess. PALMER: Is that particularly true, do you think, of the humorous writer? McFARLANE: Yes. The essence of humour is spontaneity, and if you start fooling around with what you hope is a humorous story you're in trouble, because the moment that labour begins to show, the story ceases to be funny. The humorous story would read as if you whipped it up without changing a word. I wrote many humorous stories for the Star Weekly and for Mcleans in just one sitting and they were always better than the ones I had difficulty with But the carefully constructed detective story, for example, is another matter entirely, or what you would call the "Class A" story, the story you would send to Harper's Magazine or Atlantic Monthly. Those are the stories you might put a little more work into. PALMER: How would you have felt if you had been asked to revise the original Hardy Boys stories? McFARLANE: I wouldn't have touched it. For one thing there was no financial necessity to do it at that time anyway. I spent most of the time writing the Hardy Boys hoping I would have sufficient financial independence to break away from them. It was a long time coming though, because that extra one hundred and fifty or two hundred dollars a month, or whatever it was, was always pretty handy, and the stories were almost ridiculously easy to write. You hardly seemed to be working at all, you could do them very quickly; and I was much too long in the business of writing them, so I spent most of my time on the Hardy Boys stories trying to get out of it. There was no way that I would have gone back to that sort of thing. I've kept a journal for years and some of the entries start with groans: "Began work on another Hardy Boys book today, oh hell," or something like that. It was drudgery, real drudgery, after a while. At first I enjoyed it, but King Clancy or someone said, "If you don't like the game, get off the ice and don't play it," and this is my feeling about it. The moment it stopped being fun, no way do you want to stay with it. PALMER: Do you have any theories as to why they continue to be so appealing to children? McFARLANE: Well, I did take trouble with the writing of them you know. Many of the writers of boys' books of that time wrote very hastily, and some of them weren't very good writers anyway. Some man who was interviewed said that Stratemeyer hired hacks, drunks and broken-down newspaper men and so on to write them. Well I think that's a bit of slander, but we weren't all that good, let's say. Of course he liked to grab an up and coming youngster like myself and get him into the racket. But I think that by and large, you know, we weren't that hot. PALMER: What intrigues me is that you say they were so easy to write. McFARLANE: Well yes. There was a constant flow of action, and I think the characters were consistent. You can rubber stamp them really. Chet Morton was always eating an apple and so on. You get that sort of thing from Dickens. Mr. Micawber always says something is going to turn up, and Uriah Heep is forever washing his hands in invisible water and so on. These are tags that you keep repeating every time a character comes on. That's how you establish well let's call it characterization. It isn't really characterization because characterization goes much deeper than that. But for the writer it's a convenient and quick way of establishing the identity of a character. PALMER: I'm interested that you mention Dickens because it occurred to me that there are several Dickensian touches in the things you have written. I am thinking particularly of the little boy in The Last of the Great Picnics who runs all his sentences together. He is described as running around in circles, as if winding himself up, and then shooting off at a tangent. McFARLANE: He's one of my favourite characters. I forget his name now, but he's on of my favourite characters and I've been trying to work out a story for a sequel to the book. Sequels are not always very fortunate, but this one has that youngster come to visit the kids on their farm and causing all sorts of commotion, because of course he is a foreign element coming in there with his wild enthusiasms. I rather like that youngster, and any time you see him he's running in circles and jumping up and down. Well we all know kids like that they're hyper. PALMER: Can I ask you a rather broad question, and that is, do you have any ideas about the special demands of writing for children? McFARLANE: Well, I have a feeling, and I may be wrong (of course this applies to everything I say I may be wrong), that if you're trying to write for children you should just sit down and tell a story, and if it happens to be about children, or fall into the category of stories children will like, then I suppose becomes a children's book. But to sit down to write a book specifically for children can be full of danger. I have a feeling that so many so-called children's books are not really for children at all, they are written for librarians and teachers, because if you want your book to see (a child isn't going to buy it) you're going to aim it at a librarian or a teacher, the person who puts your book into the hands of the child. So there I think things get a little bit in the way of the cart before the horse. I don't think Stevenson sat down to write a boys' book when he wrote Treasure Island, which is the classic among boys' books. He sat down to write one good pirate story. Look at Henty, who was probably one of the most popular of all writers. His heroes were always young men who were in the army or the navy or who were young explorers. They weren't children, they were young English fellows, but somehow or other Henty had this great reputation as a writer of boys' books. I don't think he should be classed in that manner. If you add up the ages of his characters they definitely were not kids, and these books had an enormous appeal to children, young men, older men it went right across the scale. PALMER: Talking about ages of readers, the new versions of the Hardy Boys books have got on the back, "Any boy aged 10 to 14 will love these books" Is that the kind of age range you had in mind? McFARLANE: I never had any age range in mind at all. I was asked to write some books about two boys who were, I think, fifteen or sixteen. No, I just sat down, and this was the age of the kids, so all right. They say you should try to visualize your audience but I never did that, you just sit down and do a job of work and you write it I noticed that in one of the re-writes the boys had become a year older somehow or other. I think the reason for that was to get them painlessly, and without the necessity of passing exams, out of school. I don't believe they attend school anymore, so maybe the advance in age was done for that reason. However, I've never been in communication with the firm. I've never been very much confirmed with the educational progress of the Hardy Boys, but being as bright as they were I'm surprised they didn't go to college. In some boys' books they had the boys grow up Dave Meyer, I think, went to Yale, and there are others in which the boy as the young hero went right through high school and college and then they ran into a blind alley: where do we go from here? They either had to keep them in their senior year of college or get rid of them somehow. So the series would end. There were very few series in which the boys had any growth. I read a little thing in Rolling Stone magazine a few months ago, asking whatever happened to the Hardy Boys. I wrote and told them that I was in a position to know. I was doing a plug of course for Ghost of the Hardy Boys. I said Fenton Hardy is now living in retirement in Florida; he hasn't taken a case, although he does get the odd vague phone call from the C.I.A. the F.B.I. or the Government. Mrs. Hardy disappeared years and years ago as everyone knows. She went out to make sandwiches one day and never came back. Aunt Gertrude had a stroke while arguing with a cashier in a supermarket. Her passing is deeply regretted. As for the Hardy Boys, they have their own private consulting firm with offices and Park Avenue, and their fees are so desperately high that they charge you $25,000 just to get inside the office to talk to them, and so on crazy things like this. Rolling Stone ran it great amusement. PALMER: One last question. You've been in television, films and radio, as well as writing books. Do you think it's important that children read? Is there something special about books that is particularly beneficial? McFARLANE: I think it is particularly important now, with the competition of television, where the kid merely sits back and lets the flood of images was over him. He doesn't have to exercise his imagination very greatly, and it washes over him and leaves no particularly lasting effect. Now some may learn something from television, yes I'll agree, but I don't think there's any substitute for reading in the long run. I've found in recent years that I'm looking at less television and going to the library and hauling out more books, and even going back to old books and re-reading The Count of Monte Cristo, for example, Pepy's Diary, and things like that books that I read and enjoyed a long time ago. I'm going back to reading them and I don't miss television that much. I'm finding television is exhausting its material, so things are spread pretty thin I don't think you can afford to sacrifice reading just because television is taking up a lot of a youngster's time. Reading is enormously important. Look at the amount of information that comes at us every day. The average morning newspaper for example has probably much more information in it than you used to find in the same paper ten to fifteen years ago far more stuff now. It's coming from all corners of the globe. All sorts of ideas are thrown at you and you have to be pretty agile to even keep up with it. A SELECTED McFARLANE BIBLIOGRAPHY The numerous early stories of adventure, sport and humour were published in such magazines as The Toronto Star Weekly, Maclean's Canadian (later The Canadian), Vanity Fair, Everybody's, Canadian Home Journal, Country Gentleman, Goblin, Liberty, Adventure, West, Red-Blooded Stories, Top Notch, Short Stories, Mystery Stories, Clues, Detective Fiction Weekly, Real Detective, All-Star Detective, Complete Detective, Dynamic Detective, Sport Story, Knockout and Thrilling Sport. Some of the hockey and northern adventure stories in the Methuen Checkmate series: Agent of the Falcon, The Dynamite Flynns, The Mystery of Spider Lake, and Squeeze Play (1975); Breakaway and The Snow Hawk (1976). The children's books written from outlines provided by the Stratemeyer Syndicate included the following "Dave Fearless" and published by the Garden City Publishing Co.: Dave Fearless under the Ocean, Dave Fearless in the Black Jungle, Dave Fearless near the South Pole, Dave Fearless on the Lost Brig, and Dave Fearless at Whirlpool Point (1926): the first four "Dana Girls" books under the name "Carolyn Keene" (Grosset and Dunlap): By the Light of the Study Lamp, The Secret of the Lone Tree Cottage, In the Shadow of the Tower (1934), A Three-Cornered Mystery (1935); one volume of the "X Bar X Boys" series, The Border Patrol (Grosset and Dunlap), under the name James Cody Ferris"; and the following "Hardy Boys" books (Grosset and Dunlap): The Tower Treasure, The House on the Cliff, The Secret of the Old Mill (1927), The Missing Chums, Hunting for Hidden Gold, The Shore Road Mystery (1928), The Secret of the Caves, The Mystery of Cabin Island (1929), The Great Airport Mystery (1930), What Happened at Midnight (1931), While the Clock Ticked (1932), Footprints under the Window (1933), The Mark on the Door (1934), The Hidden Harbor Mystery (1935), The Sinister Signpost (1936), A Figure in Hiding (1937), The Secret Warning (1938), The Flickering Torch Mystery (1943), The Short-Wave Mystery (1945), The Secret Panel (1946), and The Phantom Freighter (1947). The only one of McFarlane's many broadcast plays to be published is "Fire in the North: A Play Commemorating the Fiftieth Anniversary of the Haileybury Fire" originally produced in 1972 by the CBC radio series, "The Bush and the Salon" and published in the same year by the Highway Book shop, Cobalt, Ont. His two novels for adults are Streets of Shadow (1930) and The Murder Tree (1931), both published in New York by E.P. Dutton and in London by Stanley Paul. More recently there have been two books for children: The Last of the Great Picnics (1965, reprinted 1974), and McGonigle Scores (1966), both published in Toronto by McClelland and Stewart. McFarlane has written two autobiographical books, both concentrating on his early life: A Kid in Haileybury (Cobalt, Ont.: Highway Book Shop, 1975), and Ghost of the Hardy Boys (Toronto: Methuen/Two Continents, 1976). Finally, McFarlane's letter to Rolling Stone on the fate of the Hardy Boys (referred to in the interview) is in issue no. 224 (October 21st, 1976), p. 10, and was written in response to "The Great Hardy Boys 'Whodunit'" by Ed Zuckerman in issue no. 221 (September 9th, 1976), pp. 36-40. David Palmer is Academic Skills Counsellor at McMaster University. He has taught at the University of Guelph and McMaster, where he completed a doctoral dissertation on the concept of chivalry in medieval life and literature. Among other publications he has contributed an essay on Leslie McFarlane to the forthcoming Twentieth Century Children's Writers (St. James Press). This article originally appeared in Canadian Children's Literature * University of Guelph * Guelph, Ontario, Canada N1G 2W1 November 1978 issue |

|

You have a wonderful website! It makes me feel like an eight-year-old again (something that really shouldn't be happening for another forty years or so). I particularly enjoy your Bayport Times periodical, and look forward to each issue.

I have a little information to add to the nifty article, "A Child's Eye View of Law and Order: Crime and Criminals As Seen in the Original Hardy Boys Series (1927-58)" by Glenn Lockhart. It states that "The only time murder is ever mentioned in the original canon is very early on in the series (in volume two, The House on the Cliff Of course, not everyone considers suicide to be murder, but in one of my favorite volumes, The Sinister Signpost, the insane Mr. Vilnoff shocked me by electrocuting himself: You shall never take me alive!" he shrieked. "I vould radder die.In another of my favorites, The Disappearing Floor (OK, so I go for the bizarre ones), there are several unquestionable murders. The first one is revealed in the past tense by Mr. Hardy and Frank: Mr. Hardy examined the paper. "Well, I'm not surprised, boys. In fact, this proves just what I've suspected right along, that this cave is the hideaway of Beeson and his gang. I suspect they are guilty of having recently robbed the Wayne County Bank."Thanks for letting me share this, and especially for the blissful memories your site has provided me. - Gary Sanner Your Hardy Boys site is fantastic. I've been a big fan of the Hardys since childhood and now my son reads them too. The Bayport Times is fascinating, a true labor of love. Thank you for all your hard work. - Ron Bisig Readers - This is your forum to tell the world your thoughts on the Hardys! |

A Hardy Boys Message Board Talk About The Hardy Boys With Other Fans! |

| All Rights Reserved |

Contact the Bayport Times by E-Mail:

Leslie McFarlane, one of the world's most popular children's authors and a prolific contributor to Canadian popular culture, died on September 6th, 1977 in Whitby, Ontario. Born at Carleton Place, Ontario in 1902, he worked as a reporter for several newspapers in Ontario and Massachusetts, and from the twenties to the forties contributed hundreds of stories and serials to the "better pulps" and "smooth-paper magazines" (as Maclean's explained in 1940) in Canada, the U.S.A. and Great Britain. In this period he also published two novels, and under various pseudonyms wrote numerous children's adventure books for the Stratemeyer Syndicate of New Jersey (home of the Bobbsey Twins), including the first Hardy Boys Books.

Leslie McFarlane, one of the world's most popular children's authors and a prolific contributor to Canadian popular culture, died on September 6th, 1977 in Whitby, Ontario. Born at Carleton Place, Ontario in 1902, he worked as a reporter for several newspapers in Ontario and Massachusetts, and from the twenties to the forties contributed hundreds of stories and serials to the "better pulps" and "smooth-paper magazines" (as Maclean's explained in 1940) in Canada, the U.S.A. and Great Britain. In this period he also published two novels, and under various pseudonyms wrote numerous children's adventure books for the Stratemeyer Syndicate of New Jersey (home of the Bobbsey Twins), including the first Hardy Boys Books.