answers to Frequently Asked QuestionsWho's Who History Authors Franklin W. Dixon Edward StratemeyerChet's Hobbies Scarce Editions Reference Books Library Editions Title Check List |

Who's Who?Frank Hardy The older and more serious of the brothers, he was 16 when the series started and aged to 18 in the later stories. He is tall, dark with straight black hair and brown eyes. He is a star athlete and honor student (although he did have to repeat a grade due to illness). Joe Hardy The more impulsive of the brothers, he was 15 when the series started and stopped aging at 17. He is fair with curly hair and blue eyes. He is also a star athlete. Fenton Hardy Father of Frank and Joe. Former ace NYPD detective, he moved into private practice in Bayport. He is in his mid-40's, tall, dark, handsome, athletic and has small feet. He appears or is mentioned in every Hardy Boys story. Many, if not most, of the Boys cases have a direct connection to Fenton's current case. "Aunt" Gertrude Hardy Late-middle-aged (given as 65 in volume 10) spinster sister of Fenton Hardy. Tall, angular, sharp tongued and peppery, she is constantly visiting the Hardy household unannounced and taking over, while criticising everything in sight. Eventually she moved into the Hardy home, apparently without any objection from perennial doormat Laura Hardy. Although described as "secretly adoring" the Hardy Boys, she is practically a raving psychotic in her non-stop denunciations of them (and the world in general). I find it hard to believe that any family would let this tyrannical, paranoid harpie into their home more than once. She first appeared in volume 4, The Missing Chums, and was in every story thereafter. Laura Hardy Mother of Hardy Boys. Small, slim with blond hair and blue eyes, she is a virtual non-entity in the series, relegated to providing sandwiches to the Boys and their pals. She appears, albeit briefly at times, in all stories. So unimportant is she that she was called "Mildred" in one of the stories (The Mystery Of The Flying Express)! Chet Morton The Boys' best friend and brother of Iola, he appears in every story. Plump, good-natured, constantly eating and playing tricks, he resides with his family on a farm on the outskirts of Bayport. In the later stories Chet has a new hobby (which invariably ties into the current case) in almost every book. Chet's mother and father also appear in several stories. Iola Morton Sister of Chet and subject of Joe's fitful romantic interest. At first described as plump and dark, she evolves into a slender beauty with twinkling eyes, long hair and tilted nose. She appears in almost all stories. Iola was blown to smithereens in the first Casefiles story, although she remained alive in the Digest series. Callie Shaw Frank's romantic interest. She is a small, pretty and vivacious with brown hair and eyes. She appears in almost all stories. It should be noted that both Frank and Joe's "romantic" interests never pass the chaste, mutual admiration stage. Allen "Biff" Hooper Tall, muscular pal of the Boys and one of the "gang". He excels at boxing, wrestling and football. Owner of the motor boat "Envoy". He appears in most stories. Tony Prito Pal of the Boys and one of the "gang". Amiable, fearless, dark-haired son of Italian immigrants, he is the skipper of the motor boat "Napoli" (owned by his father). He spoke with an accent in the early stories but this vanished after a while. He appears in most stories. Phil Cohen Pal of the Boys and one of the "gang". A diminutive, black-haired Jewish boy, he appears in many stories. Jerry Gilroy Tall, athletic, baseball-loving pal of the Boys and one of the "gang". He appears in some stories. Chief Ezra Collig Chief of the Bayport PD. The early stories describe him as a somewhat slow-witted, pompous martinet, who was jealous of the Boys success. In the later stories he evolved into "canny police officer" and friend of the boys. He appears in many stories. Detective Oscar Smuff Thick-headed stooge of Chief Collig. He was demoted to patrolman (and even civilian!) as the series went on. He appears in some stories. Officer Con Riley Slow-witted and self-important, he is often the target of pranks played by the Boys and their pals. He appears in quite a few stories. Tom Casey Mounted Bayport policeman. He appears in a few stories, starting with #22. Perry "Slim" Robinson The Boys cleared his father in the Tower Treasure case. He appears in 4 stories, ending in volume 10. Jack Dodd Cleared by the Boys in the Shore Road car theft case. He appears in volumes 6 & 7. Dick Ames Friend of Boys. Appears in volumes 22 & 27. Hurd Applegate Wealthy, eccentric stamp collector and owner of the Tower Mansion. He appears in volumes 1, 6, 9 & 11. His sister, Adelia, appears in volumes 1 & 6. Dr. Bates Hardy family physician. He appears in volumes 12 & 18. Warden Duckworth Of Delmore prison, friend of Mr. Hardy. He appears in volumes 31 & 36. Amos Grice Elderly storekeeper. He appears in volumes 8 & 9. Elroy Jefferson Stamp collector and owner of Cabin Island. He appears in volumes 8 & 9. Sam Radley Mr. Hardy's top investigator. He appears in several stories. Jack Wayne Mr. Hardy's charter plane pilot. He appears in several of the later stories. Jadbury Wilson Geezer and former gold miner. He appears in volumes 5, 6 & 28. The Sleuth The Boys' prized motor boat, purchased with the rewards earned in the first 2 volumes. It is described as a sleek, speedy craft with smooth lines and a powerful, if at times faulty, engine. The Sleuth appears in many stories and appears to be jinxed, causing terrible storms to suddenly blow up nearly every time the Boys take her out. Bayport The Boys' home town and the most crime-infested city on the northeastern seaboard. A thriving town of 50,000 residents located on Barmet Bay, it is home to the most changable and inhospitable weather known to man. It is surrounded by farms, rivers, cliffs and even has its own airport & seaport. The large, comfortable Hardy home is located at the intersection of High & Elm Streets.

|

| |||

| 1926 | Edward Stratemeyer conceived the idea for the Hardy Boys and created the outlines for the first stories. After answering a newspaper advertisement a Canadian newspaper writer, Leslie McFarlane, was hired by Edward Stratemeyer to ghostwrite the stories for a flat payment of $125 each, a sum that was increased over the years. McFarlane continued to write the stories from Syndicate supplied outlines, with brief interruption, for the next twenty years. | ||

| 1927 | The first three "breeder" volumes of the Hardy Boys, The Tower Treasure, The House On The Cliff, The Secret Of The Old Mill, are released in May (© May 16) by Grosset & Dunlap. The books were published in a red binding with a black shield lettered "The Hardy Boys Stories" and have plain white endpapers. The dustjackets and glossy frontispieces were illustrated by Walter S. Rogers, who did art for many G&D series at the time. DJ's have white spine with red shield. | ||

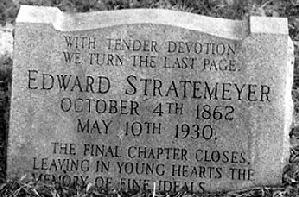

| 1930 | Edward Stratemeyer dies on May 10. Syndicate taken over by his daughters, Harriet and Edna. | ||

| 1932 | Introduction of brown binding with silhouettes of boys and illustrated endpapers by J. Clemens Gretta with a scene of a boy with binoculars peering across a river. Last red volume #11, While The Clock Ticked. These were reprinted in brown from this time on, as were the originals beginning with #12, Footprints Under The Window. First printing of Gretta endpapers was in brown ink; all subsequent printings were in orange or red-orange. | ||

| 1934 | Introduction of yellow spine DJ's on #13, The Mark On The Door. Reprints of #1-12 retain white spine.

It should be noted that the so-called "yellow" spine varied from deep orange to yellow depending on the book. | ||

| 1941 | Volumes 1-12 reprinted with yellow spine DJ's | ||

| 1942 | Introduction of wartime paper. | ||

| 1943 | All books reprinted on thinner paper. Cover boards also thinner. Introduction of Wartime Conditions notice on second 1943 printing. | ||

| 1944 | New cover art and frontispieces for Vols 1-7 and 9. Glossy frontispieces replaced by frontispiece on plain paper in these. | ||

| 1945 | New cover art for volume 8, The Mystery Of Cabin Island. Wartime notice deleted from second 1945 printing. | ||

| 1946 | Introduction of wraparound scene DJ on #25, The Secret Panel. New art for #10, What Happened At Midnight | ||

| 1948 | Wartime paper ends. | ||

| 1950 | New cover art by Bill Gillies for #11-15 | ||

| 1951 | Introduction of light tan "tweed" binding. Books have thinner cover boards and are no longer sewn. First printing of #30, The Wailing Siren Mystery, is last of brown books. | ||

| 1953 | Breaking with a 23 year tradition, 2 titles instead of 1 were released: Crisscross Shadow and Yellow Feather Mystery. | ||

| 1955 | First of two Walt Disney Mickey Mouse Club Hardy Boys TV serials, The Mystery Of The Applegate Treasure, aired. The serial was based on The Tower Treasure. This series was responsible for the first of the Hardy Boys collectible items (games, rings, coloring books, etc.) | ||

| 1956 | First Hardy Boys comic book ever published, The Hardy Boys by Walt Disney, released. | ||

| 1957 | Second of two Walt Disney Mickey Mouse Club Hardy Boys TV serials, The Mystery Of Ghost Farm, aired. This serial was entirely original and was not based on any Hardy Boys book.

Length of books shortened from approximately 220 pages to approximately 180 pages starting with #37, The Ghost At Skeleton Rock. | ||

| 1958 | Gretta endpapers replaced by brown multi-picture endpapers on all volumes.

First year since the series was introduced that no new title was released. | ||

| 1959 | Revised, shorter texts for The Tower Treasure and The House On The Cliff released.

First Hardy Boys spin-off book, Detective Handbook, released. Walt Disney Hardy Boys comic series discontinued after 4 issues. | ||

| 1961 | Introduction of white multi-picture endpapers on revised edition of #14, The Hidden Harbor Mystery.

Introduction of pictorial cloth, or "picture cover" binding on all Hardy Boys books, new and reprint. Most original text stories have brown endpapers; revised text and originals from #41 (The Clue Of The Screeching Owl) on had white endpapers. | ||

| 1965 | Chet Morton spin-off series proposed. The series never went beyond the discussion stage. Titles proposed were:

Chet Morton and the Funny-Putty Caper Chet Morton and the Talking Turkey Chet Morton and the Mighty Muscle-Builder Chet Morton and the Stolen Flea Circus Chet Morton and the Electronic Exam-Passer Chet Morton and the Bird-Brain Blimp Chet Morton and the Monkey's Uncle Chet Morton and the Flying Bike |

||

| 1967 | Pilot show for a new Hardy Boys TV show (The Mystery Of The Chinese Junk) aired. The proposed series never made it to the air. | ||

| 1969 | The Hardy Boys animated TV series first aired on the ABC network. This series generated many collectible items. | ||

| 1970 | First Gold Key Hardy Boys comic book released. | ||

| 1971 | Animated series goes off the air.

Gold Key Hardy Boys comic book series discontinued. | ||

| 1973 | White multi-scene endpapers now on all editions. | ||

| 1976 | Ghost Of The Hardy Boys, the autobiography of Leslie McFarlane, published.

Grosset & Dunlap published book club editions of vols. 1-3 with dustjackets. | ||

| 1977 | First episode of The Hardy Boys Mysteries, starring Shaun Cassidy & Parker Stevenson, aired. This series generated an enormous amount of Hardy Boys collectibles and memorabilia.

Leslie McFarlane dies on September 6. | ||

| 1978 | Grosset & Dunlap released 9 volume 2-in-1 book club set.

Grosset & Dunlap released the 3 volume Hardy Boys Favorite Classics picture cover books, each with a preface by Franklin W. Dixon. | ||

| 1979 | Last new Hardy Boys title (#58 - The Sting Of The Scorpion) published by Grosset & Dunlap released although G&D retained the right to keep publishing the first 58 stories and the Detective Handbook.

Endpapers changed to cameo with picture of the boys. First books (commonly called digests) from Simon & Schuster's Wanderer imprint appear, starting with #59, Night Of the Werewolf. These were released in both paperback & hardcover DJ versions. Scholastic Books also issued an edition of Volume 59 in November (reprinted in 6/80). The Hardy Boys Mysteries TV series goes off the air. | ||

| 1980 | A Hardy Boys Handbook Seven Stories Of Survival released in both paperback and hardcover DJ versions.

December 16 issue of Family Circle magazine contains Nancy Drew And The Hardy Boys Solve A Christmas Mystery. | ||

| 1981 | First volume of Nancy Drew And The Hardy Boys Super Sleuths series released. | ||

| 1984 | Hardy Boys Ghost Stories released.

Nancy Drew And The Hardy Boys Camp Fire Stories released. Nancy Drew And The Hardy Boys Super Sleuths series discontinued after 2 volumes. First volume of the Nancy Drew And The Hardy Boys Be A Detective Stories (The Secret Of The Knight's Sword) series released. | ||

| 1985 | Simon & Schuster discontinues production of hardcover DJ versions of Digests, ending with #85 The Skyfire Puzzle.

Nancy Drew And The Hardy Boys Be A Detective Stories discontinued after 6 volumes. | ||

| 1986 | Second year since the series was introduced that no new title was released. | ||

| 1987 | Volumes 1-58 now have laminated plastic covers (often called "glossy" or "flashlight" binding) and blank endpapers.

The Detective Handbook was reduced to the same size as the rest of the books. Easton Press produces a limited edition set of leather bound, slipcased copies of the first twelve stories. Digests now issued under Simon & Schuster's Minstrel imprint. First Hardy Boys Casefile (Dead On Target) released. | ||

| 1988 | First Nancy Drew & Hardy Boys Supermystery (Double Crossing) released. | ||

| 1991 | Applewood Books begins publishing it's First Edition facsimile series, starting with the The Tower Treasure, The House On The Cliff and The Secret Of The Old Mill | ||

| 1992 | First Hardy Boys - Tom Swift Ultra Thriller, "Time Bomb", released.

Scholastic Books releases PC Book Club editions of The Tower Treasure and The House On The Cliff. | ||

| 1993 | Hardy Boys - Tom Swift Ultra Thriller series discontinued after 2 volumes.

The Hardy Boys in the Mystery of the Haunted House, a play adapted by Jon Klein from The House on the Cliff, first performed. | ||

| 1995 | Short lived syndicated Hardy Boys series produced in Canada by Nelvana first aired in September. | ||

| 1996 | The Unofficial Hardy Boys Home Page goes online. | ||

| 1997 | First Clues Brothers (The Gross Ghost Mystery) story released.

The first issue of The Bayport Times goes online. The Hardy Boys in the Secret of Skullbone Island, a play adapted by Jon Klein from The Secret Warning, first performed. | ||

| 1998 | Casefile series discontinued after 127 volumes.

Supermystery series discontinued after 36 volumes. First 3 in 1 Casefile Collector's Edition released. | ||

| 1999 | Smithmark Publishing releases a 3 In 1 Hardy Boys DJ edition containing revised versions of The Tower Treasure, The House On The Cliff, The Secret Of The Old Mill.

3 in 1 Casefile Collector's Edition series discontinued after 3 volumes. The Secret Of The Old Queen (Book by Timothy Cope, Music & Lyrics by Paul Boesing), a musical parody of the Hardy Boys mystery stories, first performed. | ||

| 2000 | Clues Brothers series discontinued after 17 volumes.

Smithmark Publishing goes bankrupt and the planned second volume of their 3 in 1 series is never released. First cover art that doesn't feature either of the Boys, Training For Trouble, #161, released. | ||

| 2001 | First Hardy Boys E-Book (#166 Past And Present Danger) released for online downloading for Adobe or Microsoft readers. | ||

| 2002 | Starting with #171, The Test Case, Digests released under Simon & Schuster's Alladin imprint. Several older Digests also were reprinted under the Alladin imprint. To celebrate the Hardys' 75th anniversary in 2002, Simon & Schuster released a "Collector's Edition" which contains The Caribbean Cruise Caper (#154); DareDevils (#159); Skin And Bones (#164) Hardy Boys Guide To Life, a mini-book of aphorisms collected from various Hardy Boys stories, released. The House On The Point: A Tribute To Franklin W Dixon And The Hardy Boys by Benjamin Hoff released. Audio cassette versions, read by Bill Irwin, of the first four revised stories released by The Listening Library (Random House). Large print hardcover versions of Digests #171, The Test Case, and #172, Trouble In Warp Space, released by Thorndike Press. | ||

| 2003 | The Listening Library continues its series of audio tapes with volumes 5-7.

Large print hardcover version of Digest #159, Daredevils, released by Thorndike Press. Mystery Box by Gordon McAlpine, fictional novel about the exploits of "Frank" Dixon and Carolyn Keene, released by Cricket Books. | ||

| 2004 |

Secret of the Hardy Boys: Leslie McFarlane and the Stratemeyer Syndicate by Marilyn S. Greenwald published.

Grosset & Dunlap releases two 3 in 1 omnibus editions - Best of Hardy Boys Classic Collection Vols. 1 & 2 Simon & Schuster publishes hardcover edition of the 2002 "Collector's Edition" for Sweetwater Press. Scholastic Books releases several Digests under their imprint: A Will to Survive, Crime In The Cards, Speed Times Five, The Test Case, Training For Trouble, Trouble In Warp Space and Typhoon Island. | ||

| 2005 |

Papercutz releases a 3 issue Hardy Boys comic book series, The Ocean Of Osyria.

Grosset & Dunlap begins reprinting Digests (#'s 59-66) in hardcover "Flashlight" format. Digest series discontinued with the publication of volume #190 Motocross Madness. The Hardy Boys: Undercover Brothers series debuts. Papercutz releases The Ocean Of Osyria and other graphic novels in hardcover and paperback formats. HerInteractive releases Last Train To Blue Moon Canyon, a Nancy Drew computer game on CD-ROM which features the Hardy Boys. First season of the 1970s ABC-TV Hardy Boys/Nancy Drew Mysteries released on DVD. Simon & Schuster releases a hardcover edition of the Casefiles Collector's Edition #2. Cover is a late "Digest file" style with the cover art from Digest #152 "Danger In The Extreme" adapted for use. | ||

| 2006 |

Spotlight Publications, the school and library distributor for Papercutz, published their hardcover editions of Graphic Novels 1-3

The 1990's Nelvana Hardy Boys TV series is released on DVD in Canada. HerInteractive releases The Creature Of Kapu Cave, a Nancy Drew computer game on CD-ROM which features the Hardy Boys. South Park parodied the Hardy Boys as the "Hardly Boys" in an October episode of the popular cable comedy show. The Walt Disney Mickey Mouse Club's The Mystery Of The Applegate Treasure serial, based on "The Tower Treasure", is released on DVD. "Read-A-Long" book/CD sets of volumes 8, 9 and 10 released by Request Audiobooks, a division of Diversified Merchandising Inc. | ||

| 2007 |

A new Nancy Drew/Hardy Boys series is introduced with Terror On Tour.

Hardy Boys/Nancy Drew Mysteries Season 2 DVD set released in June Larger size of the mini-edition of The Hardy Boys Guide To Life published by Running Press Books. Tonner Dolls releases Frank and Joe Hardy Dolls and accessories. Each doll has a list price of over $100.00! Applewood Books does not renew it agreement with Simon & Schuster and will no longer publish Hardy Boys reprints. | ||

| 2008 |

Cover format of Undercover Brothers changed with #22 Deprivation House

The Hardy Boys Mysteries, 1927-1979: A Cultural and Literary History by Mark Connelly released. Hardy Boys PC Game, The Hidden Theft, released by Dreamcatcher | ||

| 2009 |

Treasure On The Tracks game by Sega of America for the popular Nintendo DS Game System.

Dreamcatcher releases the second Hardy Boys PC game, The Perfect Crime Graphic Novel cover art style changed beginning with 18: D.A.N.G.E.R. Spells the Hangman! | ||

| 2010 | The Hardy Boys: Secret Files, a new series aimed at younger readers released in April.

Boy Detectives: Essays on the Hardy Boys and Others by Michael G. Cornelius released in July. The New Case Files graphic novel, Crawling With Zombies, released in October. | ||

| 2012 | The Hardy Boys Undercover Brother series discontinued. | ||

| 2013 | The Hardy Boys Adventures series begins with the release of a breeder set of 2 volumes in February.

Grosset & Dunlap discontinues publication of its Flashlight digest reprints. | ||

| 2015 | The Hardy Boys: Secret Files series ends in December after 19 volumes. | ||

| 2016 | New cover art for The Tower Treasure, The House On The Cliff, The Secret Of The Old Mill & The Missing Chums in May.

Clue Book series begins in April with two breeder volumes. Hardy Boys Adventures Graphic Novel #1 released in November. | ||

| 2017 | Nancy Drew/Hardy Boys Comic Series "The Big Lie" by Dynamite Entertainment begins in March.

New cover art for Hunting For Hidden Gold, The Shore Road Mystery, The Secret Of The Caves & The Mystery Of Cabin Island in October. | ||

| 2019 | September: Nancy Drew and The Hardy Boys: The Mystery of the Missing Adults by Scott Bryan Wilson (Author), Bob Solanovicz (Artist); | ||

| 2020 | First season of the streaming network HULU Hardy Boys show. | ||

| 2022 | Second season of the streaming network HULU Hardy Boys show. | ||

| 2023 | Third & final season of the streaming network HULU Hardy Boys show.

Original text versions of the first three titles entered the public domain and began to show up on Project Gutenberg and in paperback editions of varying quality. | ||

What Are Chet Morton's Hobbies?In the revised books and the later books, Chet usually has a new hobby in each book and most of the time they dovetail with the story. | |

|

03: The Secret of the Old Mill - Using a microscope

06: The Shore Road Mystery - Botany 07: The Secret of the Caves - Metal detecting 12: Footprints Under the Window - Meteorology 15: The Sinister Signpost - Jet propulsion of his bicycle 16: A Figure in Hiding - Health and exercise 20: The Mystery of the Flying Express - Astrology 22: The Flickering Torch Mystery - Building an airplane 24: The Short-Wave Mystery - Taxidermy 26: The Phantom Freighter - Fly tying 32: The Crisscross Shadow - Indian heritage 33: The Yellow Feather Mystery - Propeller sled 36: The Secret of Pirates' Hill - Skin diving 37: The Ghost at Skeleton Rock - Ventriloquism |

39: The Mystery of the Chinese Junk - Spelunking

40: Mystery of the Desert Giant - Infrared photography 44: The Haunted Fort - Painting 45: The Mystery of the Spiral Bridge - Shot-putting 46: The Secret Agent on Flight 101 - Magic tricks 47: Mystery of the Whale Tattoo - Scrimshaw 48: The Arctic Patrol Mystery - Karate 49: The Bombay Boomerang - Boomerangs 51: The Masked Monkey - Golf ball scavenging 52: The Shattered Helmet - Film-making 53: The Clue of the Hissing Serpent - Hot-air ballooning 55: The Witchmaster's Key - Cycling 56: The Jungle Pyramid - Gold artifacts 57: The Firebird Rocket - Model rocketry |

Who Wrote What? | |

|---|---|

| Harriet Stratemeyer Adams: 1R-2R, 25, 43*

John Almquist: 35-36 Priscilla Baker-Carr: 24R-26R, 28R-38R** James Buechler: 4R, 11R, 14R, 40-41 Vincent Buranelli: 20R, 22R, 49, 51, 55-57 John Button: 17-21 Richard Cohen: 32 Richard Deming: 21R William Dougherty: 31, 33 June Dunn: 29R** David Grambs: 6R, 12R, 27R, 29R**, 44 Alistair Hunter: 3R, 5R, 42 James Lawrence: 16R-17R, 19R, 37-39, 58 Amy McFarlane: 26*** Leslie McFarlane: 1-16, 22-24, 26*** Tom Mulvey: 9R-10R, 13R, 15R, 18R, 46 Jerrold Mundis: 47 Anne Shultes: 8R Charles S. Strong: 34 Andrew Svenson: 7R, 23R, 28-30, 45, 48, 50, 52-54 George Waller Jr.: 27 | NOTESR = Revised version.* Harriet Stratemeyer Adams may have had a hand in helping to rewrite and/or edit several other stories. ** Volume 29 The Secret Of The Lost Tunnel

*** Volume 26 The Phantom Freighter

Author information derived from signed release forms and other information found in the Stratemeyer Syndicate archives of the New York Public Library. |

Who Was Franklin W. Dixon?suggested readingGhost Of The Hardy Boys - For Sale by Leslie McFarlane - The autobiography of the ghostwriter of most of the first 25 stories Secret of the Hardy Boys: Leslie McFarlane and the Stratemeyer Syndicate - For Sale by Marilyn S. Greenwald - Detailed biography about Leslie McFarlane and the Stratemeyer Syndicate. |

As a boy, I imagined Franklin W. Dixon as a rather staid, tweedy, dignified old gent, toiling away on the latest Hardy opus in his book-lined study. Therefore, I was quite dismayed when my fourth grade teacher, Mrs. Rosalyn Zimmerman, informed me about the Stratemeyer Syndicate and the true nature of Franklin W. Dixon!

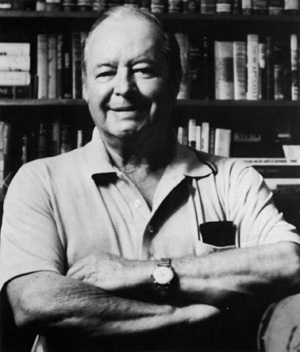

Over the years, more than 2 dozen writers, known and unknown, have assumed the mantle of Franklin W. Dixon but none was to have such an impact on the series as the first, Leslie McFarlane. Leslie Charles McFarlaneBorn: October 25, 1902 in Carleton Place, Ontario CanadaSon of John Henry McFarlane, a school principal and Rebecca (Barnett) McFarlane. Married Amy Ashmore (d. 1955) Children: Patricia, Bryan, Norah Married Beatrice G. Kenny in 1957 Died: September 6, 1977 in Whitby, Ontario Canada McFarlane began his literary career as a reporter, first in Canada and later in the United States. In 1926, he responded to an advertisement by the Stratemeyer Syndicate and soon began working for them under their popular pseudonym of Roy Rockwood on the Dave Fearless series. Later that year, he was asked by Edward Stratemeyer to ghostwrite the Hardy Boys series. He wrote wrote volumes 1-16, 22-24 and possibly volume 26, The Phantom Freighter. He received $125 each for his work on the early stories, a sum that was increased as the years went by. He received no royalties and also had to sign an agreement to not reveal his work for the Syndicate. After leaving the Syndicate, McFarlane wrote dozens of radio and TV plays for the CBC and produced and/or directed more than 50 films for the National Film Board Of Canada. In 1976, McFarlane wrote his lighted-hearted autobiography, Ghost Of The Hardy Boys, a book that is a must read for anyone who ever enjoyed a Hardy Boys story. Scott McFarlane on the origin of Franklin W. Dixon Date: 96-09-18 10:03:34 EDT

Yes. Les is my grandfather's brother. He also wrote some Ted Scott's. I read "Ghost" when it first came out, but haven't picked it up since. Les told me that it wasn't all true - had to fluff it up some to make the publisher look better than they really were (they were paying him for it, after all). You might be interested to know that the syndicate took full credit for the name (Franklin W. Dixon). Fact is Les named himself after two of his brothers (Frank - my grandfather {Franklin}, and Wilmot {also known as Dick}{both the W. and the Dixon}). This is not mentioned in "Ghost". I am aware of some of Les' other series work (Dana's, etc). HB's and TS's were his favorite works of the era. He once mentioned to me that he penned a couple of Nancy Drews, too! This caused quite a furor in the NewsGroup, as the identities of the various Carolyn Keene's over the years have had a certain cloud of mystery around them. There is really no proof that he did so, just a comment he made to me back in 1974. Personally, I think that he ghosted for another ghost, and never received credit. |

Who Was Edward Stratemeyer?suggested readingEdward Stratemeyer And The Stratemeyer Syndicate by Diedre Johnson Secret Of The Stratemeyer Syndicate by Carol Billman |

Personal Information: Born October 4, 1862, in Elizabeth, NJ; died of lobar pneumonia, May 10, 1930, in Newark, NJ; son of Henry Julius (a tobacconist and dry goods dealer) and Anna (Siegal) Stratemeyer; married Magdalene Baker Van Camp, March 25, 1891; children: Harriet Stratemeyer Adams, Edna Camilla Stratemeyer Squier. Education: Attended public schools in Elizabeth, NJ. Career: Worked in family's tobacco shop in Elizabeth, N.J., until 1889; briefly owned and managed a stationery store; free-lance writer, 1889-1930. Founder and chief executive of Stratemeyer Literary Syndicate, New York, N.Y., ca. 1906-30. The following two articles have some factual errors, nevertheless they provide an in-depth look at the man and his work. Author: Mary-Agnes Taylor, Southwest Texas State University

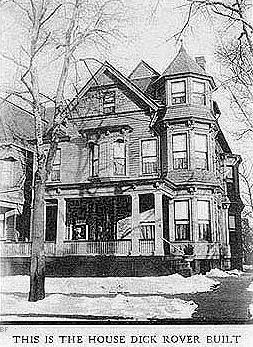

In terms of prolificacy, no author in the history of children's literature can approach the output of Edward Stratemeyer. Added to his own works, there are hundreds of series books whose plots he outlined for a highly secret, constantly changing corps of ghostwriters using house names that still remain the property of the Stratemeyer Syndicate. Available documentation attests that between the years of 1886 and 1930, Edward Stratemeyer published 150 titles that were exclusively his own and that he also masterminded a literary machine which produced some 700 titles published under more than sixty-five pseudonyms and translated into a dozen languages. In 1926, the American Library Association sponsored a survey of juvenile reading preferences, querying 36,000 children in thirty-four different cities about their favorite books; ninety-eight percent of these children responded with a Stratemeyer title. Although the syndicate's series list has greatly shrunk since World War II, figures indicate that the Stratemeyer Syndicate still sells about 6,000,000 books each year and that it has well-laid plans to carry on at that rate. Curiously, little is known about Stratemeyer's private life. He was born in Elizabeth, New Jersey, on 4 October 1862. His father, a middle-class German immigrant, migrated to California during the era of the Gold Rush but later returned to New Jersey to settle the estate of a deceased brother. Thus, young Edward Stratemeyer spent his boyhood in Elizabeth where he read with a passion the works of Horatio Alger, Jr., and William Taylor Adams Oliver Optic). The dime novel was in its heyday, and its plots were gloriously compatible with the American dream. Unlike some of the super heroes he would later create, Stratemeyer did not attend preparatory school or college, but quite like all of his leading characters, he grew up indoctrinated with the Alger-Adams dogma which proclaimed that clean living and hard work brought just rewards. He married Magdalene Baker Van Camp, and of that union two daughters were born: Harriet and Edna. Upon Stratemeyer's death, 10 May 1930, his children carried on not only the syndicate he had founded, but also the stern code of secrecy to which he adhered. After a frustrated attempt to find out something about the private life of Stratemeyer, the staff writers for the April 1934 Fortune Magazine reported the daughters were amazed at their efforts to pry. What, the new overseers of the syndicate wanted to know, would their clients think if they discovered that their revered gallery of juvenile authors was nothing but a waxworks invented by Stratemeyer? Furthermore, they felt so strongly about maintaining the illusion that, in spite of their great veneration of him, they refused to authorize any of the attempts that were then being made to write this biography. This position of secrecy was held to so firmly that once, during Stratemeyer's life, when a reader insisted upon some information about May Hollis Barton, a publisher's assistant created an entirely fabulous biography, never letting on that the "she" was in reality a kindly, stocky, nearsighted "he." In marked contrast to the sketchy information about Stratemeyer's private life, literally reams of information can be amassed about his professional life. His writing career began in 1886 while he was working at his brother Maurice Stratemeyer's tobacco shop in Elizabeth, New Jersey. Reports are that during a slow time at the store, he tore off a sheet of brown wrapping paper and began to write Victor Horton's Idea , an eighteen-thousand-word serial which he sent to the Philadelphia weekly for boys, Golden Days. A letter of acceptance, which included a check for $75.00, encouraged him to write more. His next effort, again for Golden Days, was titled Captain Bob's Secret; or, The Treasures of Bass Island. Under his own name and as Ralph Hamilton, he wrote serials for Golden Days from 1890 to 1895. The bulk of Stratemeyer's literary apprenticeship was served in writing and editing for periodicals. Contributions to Frank Munsey's Golden Argosy caught the attention of Street and Smith publishers who, in 1893, offered him the editorship of Good News. His stories built the magazine's circulation to more than 200,000. In 1895, he edited Street and Smith's Young Sports of America, later entitled Young People of America, and in 1896 he added the editorship of Bright Days. During this time, he was advancing his penchant for pen names. Many of the dime novels that he wrote for Log Cabin Library were signed Ralph Bonehill or Allan Chapman and he used the female pseudonym Julia Edwards for his women's serials in the New York Weekly. Probably the greatest advantage of his association with Street and Smith, however, was his exposure to the literary idols of the time--Frank Dey, creator of dime novel detective hero Nick Carter; Upton Sinclair, who wrote the True Blue series as Ensign Clark Fitch, USN; prolific dime novelist Edward S. Ellis; William Taylor Adams; and Horatio Alger himself. When Alger and Adams died, Stratemeyer was chosen to complete their unfinished works. He edited two Optic novels and completed An Undivided Union (1899), the final volume in Adams's Blue and Gray--On Land series. From notes and outlines he finished eleven books in the Rise of Life series under Alger's name. Meanwhile, he had not neglected his own creations. By the end of 1897, he had six series and sixteen hardcover books in print, but it was in 1898 that his big breakthrough came. Stratemeyer had written a book about two boys on a battleship and submitted it to Lothrop, Lee and Shepard. A short time thereafter, the press announced Admiral Dewey's victory at Manila Bay. Almost immediately Stratemeyer received a letter of acceptance from the publishers with the request that he revise the manuscript to parallel Dewey's victory. Thus teenaged Larry Russell and his pals were transferred to the scene of the Pacific Fleet, and Under Dewey at Manila; or, The War Fortunes of a Castaway (1898) became volume one of the Old Glory series. The book went through multiple printings, and its characters were ubiquitous in sequels, charging up SanJuan Hill, serving under Commodore Schley aboard the Brooklyn, returning to the Philippines with General Otis, riding into Santa Cruz with Major General Lawton, and finally serving on General MacArthur's staff in Luzon. Recognizing the popular appeal of war and patriotism, Stratemeyer dashed off in addition to the six Old Glory titles (1898-1901), two Minute Boys books (1898-1899); four in the Soldiers of Fortune series (1900-1906); three on the Mexican War (1900-1902); and six which formed the Colonial series (1901-1906). These early books are important in two respects: they are crammed with well-researched facts and they make use of some literary techniques that mark virtually all of the author's later works. From the very beginning of his writing career Stratemeyer had the voice of a storyteller, speaking personally to the reader, and that I-you tone was a note that sounded regardless of title or pen name. He spoke directly to his reader first in the preface of the book and then periodically in the text. Routinely, the preface of volume one carried the good news of more books to come, although two or three volumes were often published simultaneously to see if a series was going to succeed. The preface of all books beyond volume one carried the message that this book was "a complete story in itself"; however, there were others the reader would surely not want to miss. Brief summaries of the other volumes followed. In case a reader skipped the preface, the same message was slipped into the text of the story in several places. For example in On the Trail of Pontiac; or, The Pioneer Boys of the Ohio (volume four of the Colonial series, 1904), the author neatly inserts on page four, "This was at the time that George Washington, the future President of our country, was a young surveyor, and in the first volume of this series, entitled 'With Washington in the West,' I related how Dave fell in with Washington and became his assistant, and how, later on, Dave became a soldier to march under Washington during the disastrous Braddock campaign against Fort Duquesne." Page five mentions volume two, Marching on Niagara (1902), and gives the particulars of volume three, At the Fall of Montreal (1903). In both books the heroes, Dave Morris and his cousin Henry, fight bravely to defeat the French and in the fourth volume are now ready to move with their elders in the peaceful reestablishment of a family trading post. But trouble lurks in the persons of the powerful Indian chief, Pontiac, and a disgruntled Frenchman: "I shall show them that, though France is beaten, Jean Bevoir still lives.... The trading-post on the Kinotah with its beautiful lands, shall be mine--the Morrises shall never possess it!" Fast-paced battle scenes pepper the historical books, but the scenes are reported in a straight-forward, objective fashion with no attempt to exploit gory details. The works are replete with clichés, and although the following examples are from On the Trail of Pontiac, they can be found again and again in other books. "The Indians are on the warpath and they mean business." No matter how threatening a life-and-death situation, the characters are repeatedly described as "in a pickle." They take to the wilderness as "ducks take to water," but, nevertheless, often find themselves "striking their heads against a stone wall." Still, "no two ways about it," the culprits are bound to be apprehended and will "turn over a new leaf." Stratemeyer's, and the syndicate's, choices of antagonists offer clues about existing attitudes toward various ethnic groups. Just as feelings toward Jews would filter through later in the Tom Swift series, the Colonial series reflects feelings toward the French and the Indians. Although he includes a token number of good Indians in On the Trail of Pontiac, his general attitude is suggested by young Henry Morris's report that "Sam Barringford says we won't have any real peace until the redskins have had one whipping they won't forget as long as they live." Sam is a man who knows the situation; he has lived among the natives since he was six years old. Though some of the stylistic devices of the early books may be faulted by the modern reader, it should be noted that at the time of their publication the books received high praise from well-respected sources. But the astute businessman in Stratemeyer did not let the praise mislead him. War stories and even the Alger rags-to-riches themes were becoming dated. He needed fresher ideas with which the new generation of teens could identify. Although he had no such schooling himself, he outlined several series about upper-middle-class students. The fifteen-volume Dave Porter series (1905-1919), the six-title Lakeport series (1904-1912), and the six Putnam Hall books (1901-1911) enjoyed wide readership, but their success was modest compared with Stratemeyer's favorite of all series: the Rover Boys series for Young Americans (1899-1926). It is believed that the pen name for the Rovers and the Putnam Hall books--Arthur M. Winfield--was suggested by Stratemeyer's mother. The Arthur was simply for author; the M. he hoped would represent the sale of a million copies; and Winfield was literally for winning the field. His hopes were more than fulfilled. Between the publication of the first three volumes late in 1899 and the publication of the last volume in 1926, sales ran somewhere between five and six millions of copies. In all there were thirty volumes in the series. The first twenty dealt with the adventures of the three brothers, Dick, Tom, and Sam and the last ten with their respective children. The tone and the nature of the series is reflected in the introduction, which in volume one reads: MY DEAR BOYS: "The Rover Boys at School" has been written that those of you who have never put in a term or more at an American military academy for boys may gain some insight into the workings of such an institution. While Putnam Hall is not the real name of the particular place of learning I had in mind while penning this tale for your amusement and instruction, there is really such a school, and dear Captain Putnam is a living person, as are also the lively, wide-awake, fun-loving Rover brothers, Dick, Tom, and Sam, and their schoolfellows, Larry, Fred, and Frank. The same can be said, to a certain degree, of the bully Dan Baxter, and his today, the sneak commonly known as "Mumps." The present story is complete in itself, but it is written as the first of a series,. to be followed by "The Rover Boys in the Jungle," in both of which volumes we will again meet many of our former characters. Trusting that this tale will find as much favor in your hands as have my previous stories, I remain,

Possibly motivated by his fondness for the Rovers, he began, toward the end of the series, to sign his introductions Edward Stratemeyer instead of Arthur M. Winfield, a revelation which he assiduously forbade the parade of ghostwriters that populated the syndicate he established shortly after his creation of The Bobbsey Twins series. The popularity of the Bobbsey Twins books, the first of which was published in 1904, probably convinced Stratemeyer that no one writer could keep pace with prodigious literary visions he entertained. In 1906 he established the Stratemeyer Syndicate. His practice was to outline plots and mail these to fledgling writers who were sworn to secrecy and paid from $50.00 to $250.00 per book. Regardless of future sales, all rights to both pen names and book royalties belonged to the syndicate--a condition of considerable significance in view of the fact that the Bobbsey Twins is one of the series that continued publication after World War II and which to date has sold, according to various estimates, from thirty to fifty million copies. After formation of the syndicate, it becomes more difficult to say which books Stratemeyer actually wrote, but it is reasonably certain that he masterminded and edited all the volumes produced before his death. A parade of series filled the time between the Bobbsey Twins, begun in 1904, and another of his greats--the Tom Swift series. In 1910 Stratemeyer directed his assistant, Howard Garis, to drop other work and begin the scientific research necessary for the Tom Swift series. The first volume, Tom Swift and His Motor-Cycle, appeared later that year. Hero Tom Swift, a virtuous Anglo-Saxon boy who never attended college, is a mechanical genius unhampered by a lack of money and blessed with an imagination that deals easily with motorcycles, airplanes, speedboats, photo telephones, war tanks, and other ingenious devices. He was patterned after Stratemeyer's idol, Henry Ford, and many of his inventions later came into being. In fact, only twice in the thirty-eight-book series did Tom attempt to realize ideas that were not workable then or in the future. These were a process for using lightning to make artificial diamonds and the creation of a silent airplane engine. There is one major invention featured with each book. Always there is a thrilling chase and a villain trying to steal or ruin Tom's work. In fact, this series, published under the pseudonym Victor Appleton, contains a catalogue of some of the most wicked villains ever created for juvenile fiction. In addition to the murderous Jew, Greenbaum, there are, as Arthur Prager puts it in "Bless My Collar Button, If It Isn't Tom Swift!" (1976), felons of every stamp: arsonists, bushwhackers, kidnappers, bank robbers, and even a molester who tried to force his attentions on Mary. In the first few books, before Tom had hit his stride, the nemesis was bully Andy Foger, a boy about Tom's age. The grownup heavies came later. In the war there were German spies, and afterward there were unscrupulous business competitors. By manipulating the villains, Stratemeyer was able to work off some of his own prejudices. Tycoons in fancy clothes were usually swindlers. Foreigners were to be avoided or mistrusted.

Other common prejudices of the time are evident in nonvillainous characters. These are usually slapstick, eye-rolling blacks such as Tom's faithful servant, Rad, and Dinah, the Bobbseys' cook. Over the years, these characters were changed in later printings to meet the social demands of the time. Most secondary characters became less ethnically stereotyped; however, the slapstick actions, the low comedy puns, and the cliff-hangers remained. Although some recent critics judge the Tom Swift books to be Stratemeyer's best work, some of his contemporaries took a radically different view. James E. West, Chief Scout Executive for the Boy Scouts of America, considered the mass-produced series books an exploitation of juvenile taste and a danger to character development. Thus, in moral defense of his young charges, he organized the Library Commission of the Boy Scouts of America. Franklin K. Mathiews, chief librarian of the BSA, presented publishers with an approved Boy Scout list of books which did not include the Stratemeyer Syndicate's Boy Scout series. The mystery, murder, and arson in these books Mathiews considered very unscoutlike, and in 1914 he wrote for the Outlook an emotionally charged diatribe entitled "Blowing Out the Boys' Brains." Stratemeyer's sales dropped, but he countered with his own approved list. With his near monopoly threatened, he altered his approach; future series would tone down danger, thrills, and violence. It is impossible to say whether the criticism or praise of the series books should be directed specifically toward Stratemeyer or toward his writers. Gradually, more and more material surfaces about the ghostwriters, as they or researchers seek to bypass the old oaths of silence. John T. Dizer in his Tom Swift & Company, "Boys' Books" by Stratemeyer and Others (1982) says that Stratemeyer usually made a point of writing at least one book in each series. Dizer further reports that "Tom's name came from an 1894 Stratemeyer Serial, Shorthand Tom. Howard Garis ... did much contract writing for Stratemeyer and apparently was involved in about thirty-six of the forty books in the original Tom Swift Series." Dizer deplores the controversy "over who actually wrote the Motor Boys and Tom Swift": "Stratemeyer personally read and edited all his books and then issued them under one of his many house names. There is no question that Howard Garis [and many others] wrote for Stratemeyer.... However, it should be remembered that these books were written under contract to Stratemeyer, based on characters and plots developed by him; the format and even the main situations were his." The National Union Catalog, Pre-1956 Imprints offers no clarification on the problem of authorship. The entry for the Tom Swift series reads "see Victor Appleton, pseudonym" and lists Appleton titles separately. Similarly, the Bobbsey Twins entry refers the reader to "Laura Lee Hope, pseudonym," under which the titles are listed. One point, it seems, can be made with certainty; until his death, Stratemeyer was in firm control of the syndicate and its writers, and he most certainly did not allow negative criticism to erode his empire. By 1927, Stratemeyer had regained his place as ruling champion of the juvenile audience; however, he was as yet to create two detective series that would outsell all previous listings except the Bobbsey Twins. These were the Nancy Drew and the Hardy Boys books. Again, in these series it is uncertain who wrote which titles. In January 1969, Arthur Prager's Saturday Review article "The Secret of Nancy Drew" attributed authorship of the Nancy Drew series to Harriet Stratemeyer Adams, Andrew Svenson, and four anonymous ghostwriters, all writing under the name of Carolyn Keene. The article drew a personal response from Mrs. Adams, as Prager reports in his 1971 book, Rascals at Large: "Mrs. Adams pointed out that my remark about Nancy being written by her, Mr. Svenson, and four anonymous ghostwriters was incorrect. Although the Syndicate uses contract writers for some of its series, she does all the Nancys herself, and has done so since the death of her father, the late Edward Stratemeyer, who was Nancy's creator, and who wrote the first three books of the series." (Editor's Note: Harriet was shown to be a liar when later evidence proved that Mildred Wirt wrote most of the earlier Drew books. RWF) For the Hardy Boys Stratemeyer received a different sort of credit. All of this series was written by Leslie McFarlane, a shade who wrote and told all in his 1976 autobiography, The Ghost of the Hardy Boys. Under the pen name of Frank W. Dixon, McFarlane had produced other books for the syndicate, but he believed that they were inferior works. He decided that he would give his best to the Hardy Boys. When no notice or praise came for his extra effort, he was disappointed. He rationalized that Stratemeyer considered the books his own and not McFarlane's. McFarlane contented himself with the implied compliment of receiving assignments beyond the first three "breeders," but he had not the slightest notion that by half a century later the series would have run to sixty volumes and he would have written the first twenty. The pay remained at the fixed price--$150.00 per book. Faithfully, McFarlane sent in the manuscripts; he put the finished books on a special shelf and never bothered to reread them. Rather oddly he recalls, It was not until sometime in the 1940s, as a matter of fact, that I had discovered that Franklin W. Dixon and the Hardy Boys were conjurable names. One day my son had come into the workroom, which had never been exalted into a "study," and pointed to the bookcase with its shelf of Hardy Boys originals. "Why do you keep these books, Dad? Did you read them when you were a kid?" "Read them? I wrote them." And then, because it doesn't do to deceive any youngster, "At least, I wrote the words." In any evaluation of Stratemeyer's literary contribution, one must admit that ever since the days of the Mathiews attack, verbal battles have raged over the value of syndicated books. In the spring 1974 issue of the Journal of Popular Culture, Peter Soderbergh has detailed the interesting history of opinions which have fluctuated madly from 1914 through 1974. Clearly, no one can claim that the books are great literature, but, equally clearly, no one can deny that they have provided great entertainment and have been among the most popular and enduring contributions to the world of juvenile books. In a 1978 article in Children's Literature, Ken Donelson has presented an impressive list of short writings that give isolated glimpses of Edward Stratemeyer, and in Tom Swift; & Company, John Dizer offers extensive bibliographies of Stratemeyer's works, but a definitive biography of this American pied piper of print remains to be written.

"If anyone ever deserved a bronze statue in Central Park, somewhere between Hans Christian Anderson and Alice in Wonderland," declares Arthur Prager in Saturday Review, "it is Edward Stratemeyer, incomparable king of juveniles." Between 1886, when he wrote his first story on wrapping paper in his family's tobacco shop, and his death in 1930, Stratemeyer wrote, outlined, and edited more than 800 books under sixty-five pseudonyms, plus myriad short stories. His beloved creations include Dick, Tom, and Sam Rover (the Rover Boys), Bert, Nan, Freddie, and Flossie Bobbsey (the Bobbsey Twins), Tom Swift, Bomba the Jungle Boy, Frank and Joe Hardy, and Nancy Drew. John T. Dizer, writing in Tom Swift & Company: "Boys' Books" by Stratemeyer and Others, calls the literary syndicate that he founded "the most important single influence in American juvenile literature." "As oil had its Rockefeller, literature had its Stratemeyer," eulogized Fortune magazine shortly after his death. "The bulk of Stratemeyer's literary apprenticeship was served in writing and editing for periodicals," explains Dictionary of Literary Biography contributor Mary-Agnes Taylor. His initial success--his first story sold to Golden Days, a Philadelphia weekly paper for boys, for $75--encouraged the young author to write more stories. He soon became a regular contributor to Frank Munsey's periodical Golden Argosy and, in 1893, the magazine and dime novel publishers Street & Smith offered him the editorship of their journal Good News. By 1896 he was also editing the Street & Smith periodicals Young Sports of America (which became Young People of America) and Bright Days, as well as contributing women's serials to the New York Weekly under the pseudonym Julia Edwards, and dime novels under the pseudonyms Captain Ralph Bonehill and Allen Chapman, as well as under his own name. "Perhaps the greatest advantage of his association with Street and Smith, however," continues Taylor, "was his exposure to the literary idols of his time," including Frederic Van Rensselaer Dey, "creator of dime novel detective hero Nick Carter; Upton Sinclair, who wrote the True Blue series as Ensign Clark Fitch, USN; prolific dime novelist Edward S. Ellis; William Taylor Adams; and Horatio Alger himself." After the deaths of Adams and Alger, Stratemeyer was chosen to complete some of their unfinished manuscripts, using the pseudonyms Oliver Optic and Horatio Alger, Jr. Stratemeyer's success as a novelist came in 1898, during the Spanish- American War. "War was glamour in those days. Uniforms were splendid, and battles were glorious," explains Prager. The author had recently submitted a novel about several young men serving on a battleship to Lothrop, Lee & Shepard, a publishing house in Boston, when news of Admiral Dewey's victory over the Spanish fleet at Manila Bay reached the U.S. The publishers wrote the author, inquiring if he could revise his story to reflect Dewey's victory. Stratemeyer did, and Under Dewey at Manila; or, The War Fortunes of a Castaway, featuring Larry and Ben Russell and their chum Gilbert Pennington, became "the financial hit of the juvenile publishing industry in 1899," according to Prager. Popular demand brought the boys back for many more adventures in the "Old Glory" and the "Soldiers of Fortune" series, and Stratemeyer further exploited the market for war stories with books featuring boys in the French and Indian War, the American Revolution, and the Mexican War. Many were well-received by critics, including parents, teachers, and churchmen as well as the readers themselves. "These early books are important in two respects," declares Taylor. "They are crammed with well-researched facts and they make use of some literary techniques that mark virtually all of the author's later works." Stratemeyer directly addressed the reader in the introductions of his books, and his voice often interrupted the text. Frequently the story's action paused near the beginning of the volume to allow the narrator to recap the hero's previous adventures, and each account included an advertisement for the next volume in the series. Stratemeyer's prose was also rather stilted, reflecting his early association with Alger and Adams at Street & Smith, and he often relied on stereotyped views of various ethnic groups. "Except for Alger himself," declares Russel B. Nye in The Unembarrassed Muse: The Popular Arts in America, "no writer of juvenile fiction had a more unerring sense of the hackneyed." Whatever the drawbacks of Stratemeyer's prose, his work became highly popular with young readers. Late in 1899, realizing that the attraction of contemporary war stories was likely to be temporary, he introduced the "Rover Boys Series for Young Americans" under the pen name Arthur M. Winfield. These books chronicled the adventures of three brothers--Dick, Tom, and Sam Rover--at Putnam Hall, a military boarding school, and later at midwestern Brill College, and they captured the imaginations of turn-of-the- century adolescent Americans in a way no other series heroes had before. "Between the publication of the first three volumes late in 1899 and the publication of the last volume in 1926," reports Taylor, "sales ran somewhere between five and six millions of copies." The brothers, described as "lively, wide-awake American boys" by the author, were supported by a memorable cast of characters, including Dora Stanhope, and Grace and Nellie Laning, their sweethearts, their chums John "Songbird" Powell and William Philander Tubbs, and assorted bullies and other villains: Josiah Crabtree, Tad Sobber, Jesse Pelter, and Dan Baxter, among others. Stratemeyer originally conceived the "Rover Boys" series in the vein of Tom Brown's Schooldays, depicting youthful adventures, games and hijinks, but he also featured elements of melodrama and detective fiction, claims Carol Billman in The Secret of the Stratemeyer Syndicate: Nancy Drew, the Hardy Boys, and the Million Dollar Fiction Factory. Many volumes featured searches for missing people or buried treasure; The Rover Boys in the Jungle, for instance, took our heroes to Africa in search of their father. The Rovers and their friends "faced unprecedented dangers," explains the Literary Digest. "As the fun-loving Tom expressed it, on the historic occasion when an avalanche was rolling down on them from above, their cabin was in flames, Dan Baxter and his cronies were taking pot-shots at them from across the canyon, Dora Stanhope was clinging to the edge of the cliff, and the battle-ship Oregon was still ten miles away, `Well, we're in a pretty pickle, and no mistake!"' "But always, to our immense surprise," the Digest concludes, "they would emerge unscathed, restore the missing fortune, and be rewarded by three rousing cheers and--a sop to the feminine trade--an arch look from Dora and Nellie and Grace; while the discomfited bullies, outwitted again, began plotting at once their future conspiracies, to be related in the next volume of the Rover Boys Series for Young Americans." Eventually Stratemeyer permitted Dick, Tom and Sam to graduate and to start a business together, pooling their resources to form the Rover Company. They married their girls and settled down to raise families in adjoining houses on New York's Riverside Drive. Stratemeyer went on to chronicle their children's adventures in the "Second Rover Boys Series for Young Americans," which lasted for ten volumes. However, the younger Rovers never achieved the success their fathers had, explains Prager, writing in Rascals at Large; or, The Clue in the Old Nostalgia. "The generation that had loved the Rover Boys moved on to new things. Did the Crash wipe out the Rover Company? Did their Riverside Drive houses succumb to high taxes and urban blight? We never found out."

The Rover's success encouraged Stratemeyer to create other series. "Almost as soon as the first sales figures came in," reports Prager in Saturday Review, "he was designing a dozen similar series and concocting pseudonyms. He took his basic Rover figures, changed the names, associated them with some kind of speedy vehicle or popular scientific device, and slipped them into his formula." Stratemeyer soon found that his ideas outstripped his writing capacity and began to hire independent writers to fill in his outlines. Working with "Uncle Wiggily" creator Howard R. Garis under the pseudonym Clarence Young, Stratemeyer created the "Motor Boys" series; as Allen Chapman, he devised the adventures of the "Radio Boys" and "Ralph of the Railroad" series; as Victor Appleton, the "Motion Picture Boys" and "Tom Swift" series; as Franklin W. Dixon, the "Hardy Boys" and "Ted Scott Flying Stories" series, and many others. For sports enthusiasts he produced the "Baseball Joe" books under the pseudonym Lester Chadwick, and as Roy Rockwood he created Bomba the Jungle Boy, a teen-aged Tarzan. For girls and younger readers, he introduced the "Moving Picture Girls," the "Outdoor Girls," and the "Bobbsey Twins" series, using the pseudonym Laura Lee Hope; as Alice B. Emerson he developed the "Betty Gordon" and "Ruth Fielding" series, and as Carolyn Keene he invented Nancy Drew. Stratemeyer engaged in innovative publishing strategies in order to get his many series published. "Using the kind of reasoning that would later make Henry Ford a billionaire," Prager declares in Saturday Review, "he talked his publishers into slashing the prices of the `Rover' and `Motor Boys' series from a dollar to 50 cents, relying on volume sales to make up and exceed lost profit. The plan was a smashing success. At half a dollar, kids could buy the books without going through the parent-middleman." By around 1906 demand had increased so much that Stratemeyer had to systematize his production by setting up the Stratemeyer Syndicate, "a kind of literary assembly line," Prager calls it, resembling in some ways the syndicate devised by the French writer Alexandre Dumas half a century before. Stratemeyer created plot outlines for series titles and sent to contract writers, who wrote the actual stories. They then returned the manuscript to Stratemeyer, who edited it and had it put on electrotype plates, which were then leased to the publishers. Stratemeyer retained all rights to the stories, paying his contract writers an average of one hundred dollars a book. "The whole process," Prager explains, "took a month to six weeks."

Stratemeyer's success and his factory-like writing process made enemies among those who considered themselves guardians of the juvenile mind. A few years after the Boy Scouts of America were established Franklin K. Mathiews, the Chief Scout Librarian, and James E. West, the Chief Scout Executive, contacted Grosset & Dunlap, one of Stratemeyer's chief publishers, and proposed a mass reprinting of a list of Boy Scouts Approved Books in inexpensive editions. Somewhat later, Mathiews published an article in Outlook magazine savagely denouncing juvenile fiction that did not meet his standards, although he never mentioned the Stratemeyer Syndicate by name. "Mathiews began by noting that in most surveys of children's reading, inferior books, (defined as those not found in libraries), were widely read and probably as influential as the better books," reports Ken Donelson in Children's Literature. Mathiews suggested that the poor quality of Syndicate-type fiction, revealed in the lack of moral purpose and uncontrolled excitement of the stories, could cripple a young reader's imagination "as though by some material explosion they had lost a hand or foot." "I wish I could label each one of these books: `Explosives! Guaranteed to Blow Your Boy's Brains Out,"' he declared. The Chief Scout Librarian backed up his accusations with statements from other librarians testifying to the poor quality of series books and encouraged other authors, especially Percy Keese Fitzhugh, to write series fiction, but Stratemeyer's sales remained high. He had, however, learned something from the encounter: future Syndicate series "toned down danger, thrills, and violence in favor of well-researched instruction," says Prager in Saturday Review. One measure of Stratemeyer's success lies in the fact that now, more than half a century after his death, new volumes are added yearly to series he created. The "Bobbsey Twins," "Hardy Boys" and "Nancy Drew" books continue to captivate readers, and sales are as high as ever. Despite critic's misgivings, states Prager in Rascals at Large, the books "are well worth a reappraisal in the light of current taste, and like most items handcrafted in those days, they wear like iron and last for years." "Stratemeyer's legacy--respectable or not--is read on," declares Billman, "night after night, reader after reader, generation after generation." Upon Stratemeyer's death in 1930, the Syndicate was administered by his daughters, Harriet Adams and Edna Squier. Adams remained in control of the Syndicate until her death in 1982.

|

What Books Should I Be On The Lookout For? | |

|

|

What Books Are There About The Hardy Boys? |

|

Ghost Of The Hardy Boys - For Sale

The Lost Hardys - A Concordance

Rascals At Large or, The Clue In The Old Nostalgia - For Sale

Edward Stratemeyer and the Stratemeyer Syndicate - For Sale

Stratemeyer Pseudonyms And Series Books - For Sale

Secret Of The Stratemeyer Syndicate The Hardy Boys Mysteries, 1927-1979: A Cultural and Literary History

The Mysterious Case Of Nancy Drew & The Hardy Boys

Many of these books were used in the creation of this web site. A tip of the Hardy cap and a big THANK YOU to all the authors! |

Library Editions |

| The G&D editions can easily be distinguished by the pale blue binding and extra endpapers. With the exception of the two Hardy-Swift stories, I've seen examples of every series produced in a library rebinding.

|

| ___ 01: The Tower Treasure

___ 02: The House On The Cliff ___ 03: The Secret Of The Old Mill ___ 04: The Missing Chums ___ 05: Hunting For Hidden Gold ___ 06: The Shore Road Mystery ___ 07: The Secret Of The Caves ___ 08: The Mystery Of Cabin Island ___ 09: The Great Airport Mystery ___ 10: What Happened At Midnight ___ 11: While The Clock Ticked ___ 12: Footprints Under The Window ___ 13: The Mark On The Door ___ 14: The Hidden Harbor Mystery ___ 15: The Sinister Sign Post ___ 16: A Figure In Hiding ___ 17: The Secret Warning ___ 18: The Twisted Claw ___ 19: The Disappearing Floor ___ 20: The Mystery Of The Flying Express ___ 21: The Clue Of The Broken Blade ___ 22: The Flickering Torch Mystery ___ 23: The Melted Coins ___ 24: The Short-Wave Mystery ___ 25: The Secret Panel ___ 26: The Phantom Freighter ___ 27: The Secret Of Skull Mountain ___ 28: The Sign Of The Crooked Arrow ___ 29: The Secret Of The Lost Tunnel | ___ 30: The Wailing Siren Mystery

___ 31: The Secret Of Wildcat Swamp ___ 32: The Crisscross Shadow ___ 33: The Yellow Feather Mystery ___ 34: The Hooded Hawk Mystery ___ 35: The Clue In The Embers ___ 36: The Secret Of Pirate's Hill ___ 37: The Ghost At Skeleton Rock ___ 38: The Mystery At Devil's Paw ___ 39: The Mystery Of The Chinese Junk ___ 40: Mystery Of The Desert Giant ___ 41: The Clue Of The Screeching Owl ___ 42: The Viking Symbol Mystery ___ 43: The Mystery Of The Aztec Warrior ___ 44: The Haunted Fort ___ 45: The Mystery Of The Spiral Bridge ___ 46: The Secret Agent On Flight 101 ___ 47: Mystery Of The Whale Tattoo ___ 48: The Arctic Patrol Mystery ___ 49: The Bombay Boomerang ___ 50: Danger On Vampire Trail ___ 51: The Masked Monkey ___ 52: The Shattered Helmet ___ 53: The Clue Of The Hissing Serpent ___ 54: The Mysterious Caravan ___ 55: The Witchmaster's Key ___ 56: The Jungle Pyramid ___ 57: The Firebird Rocket ___ 58: The Sting Of The Scorpion |